Een symposium, muziek, een mini-expo én een nieuw boek: Krijgstoneel van Europa is feestelijk gepresenteerd!

Op dinsdag 1 juli was het moment daar: ik overhandigde het eerste exemplaar van Krijgstoneel van Europa. Tijdgenoten over het Beleg van Breda 1624-1625 aan de burgemeester van Breda, Paul Depla. Het was de culminatie van een project waar ik met veel plezier aan heb gewerkt en waar ik met evenveel voldoening op terugkijk.

Op dinsdag 1 juli was het moment daar: ik overhandigde het eerste exemplaar van Krijgstoneel van Europa. Tijdgenoten over het Beleg van Breda 1624-1625 aan de burgemeester van Breda, Paul Depla. Het was de culminatie van een project waar ik met veel plezier aan heb gewerkt en waar ik met evenveel voldoening op terugkijk.

In een volle zaal in het Stedelijk Museum Breda stonden we stil bij 400 jaar Beleg van Breda.

Lars Tupker, Jan van Oudheusden en Marjolein ’t Hart gaven boeiende lezingen over het beleg en de Tachtigjarige Oorlog, het ensemble ‘Twee violen en een bas’ (en een extra harp!) speelde prachtige 17-eeuwse muziek en ik vertelde over de totstandkoming van mijn boek, de keuzes die ik moest maken en de uitdagingen waar ik mee te maken kreeg tijdens het schrijfproces. Na de plechtige overhandiging van het eerste exemplaar sloten we de bijeenkomst goedgeluimd af door met de hele zaal een geuzenlied te zingen over het Beleg van Breda, dat de spot drijft met de Habsburgse vijand. Met pakweg 100 stemmen lukte het aardig om de sfeer van 400 jaar geleden te doen herleven!

Tijdens de borrel na afloop kon het publiek een kijkje nemen bij de mini-expo over het Beleg van Breda en nogmaals genieten van ‘Twee violen en een bas’ (en harp dus), dat zorgde voor schitterende achtergrondmuziek. Ondertussen deed ik een interessante nieuwe ervaring op: boeken signeren.

Veel dank aan de sprekers, de muzikanten, dagvoorzitters Wouter Loeff en Monique Rakhorst, en de overige organisatie van het Stedelijk Museum Breda, Erfgoed Brabant en de Zuiderwaterlinie, met wie ik deze dag heb gerealiseerd. Ik ben trots op onze samenwerking! Dank bovendien aan allen die deze dag met hun aanwezigheid en stemgeluid hebben vereerd 😉

Krijgstoneel van Europa. Tijdgenoten over het Beleg van Breda 1624-1625, vormgegeven door YURR Studio en uitgegeven door WBOOKS, is dankzij subsidie van De Mastboom-Brosens Stichting te koop voor slechts €24,95. Volg deze link om meer over het boek te lezen en het aan te schaffen.

Antwoorden op deze en andere prikkelende vragen zijn te vinden in het nieuwe boek van Nicoline van der Sijs, Dijt onze woordenschat alsmaar uit? Over opbouw en geschiedenis van de Nederlandse woordenschat, dat tegelijk het eerste deeltje is in de nieuwe Open Access reeks ‘Nederlands in het klein’. De reeks is een initiatief van de afdeling Nederlandse Taal en Cultuur van Radboud University, en wordt uitgegeven door Radboud University Press.

Antwoorden op deze en andere prikkelende vragen zijn te vinden in het nieuwe boek van Nicoline van der Sijs, Dijt onze woordenschat alsmaar uit? Over opbouw en geschiedenis van de Nederlandse woordenschat, dat tegelijk het eerste deeltje is in de nieuwe Open Access reeks ‘Nederlands in het klein’. De reeks is een initiatief van de afdeling Nederlandse Taal en Cultuur van Radboud University, en wordt uitgegeven door Radboud University Press.

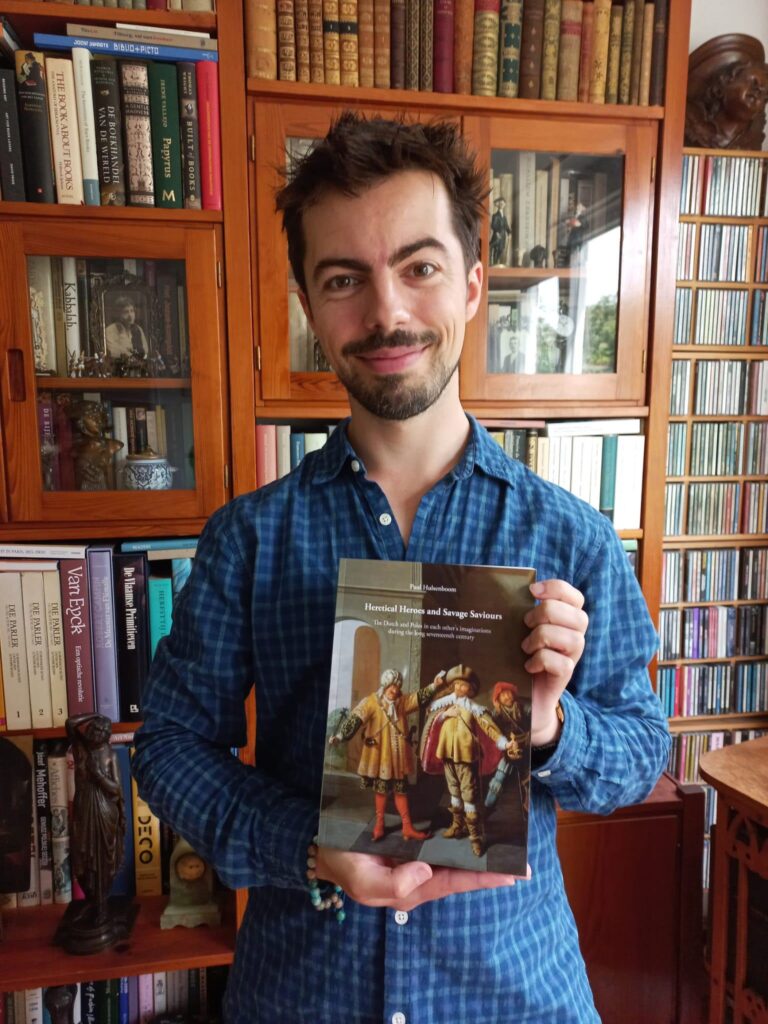

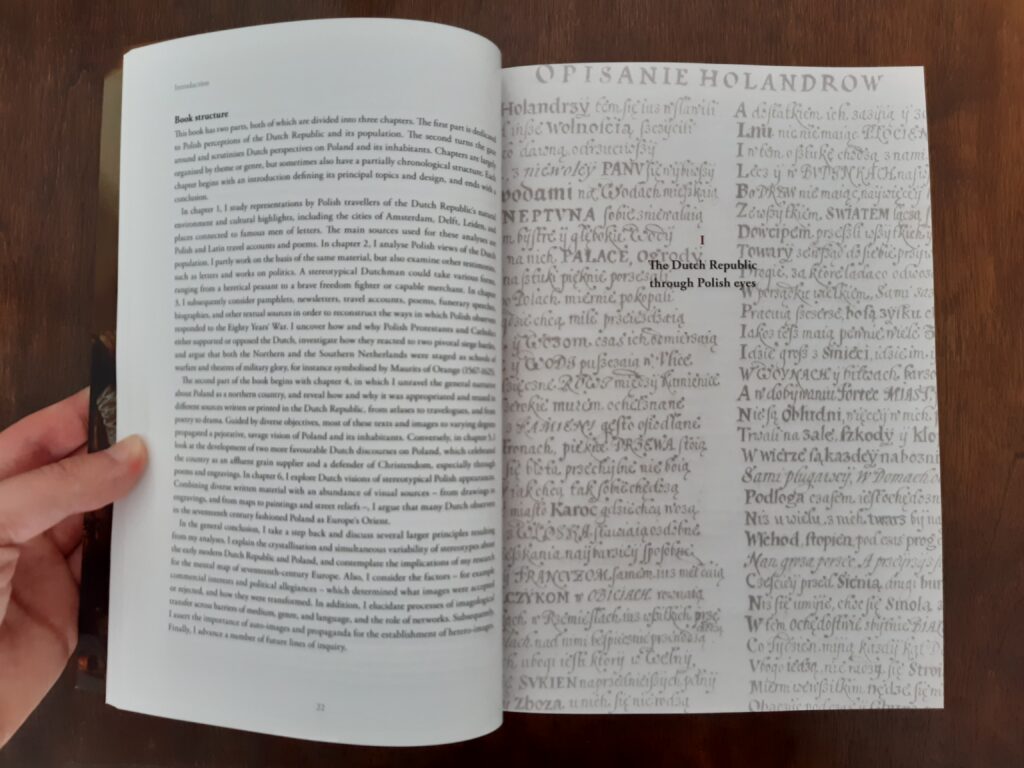

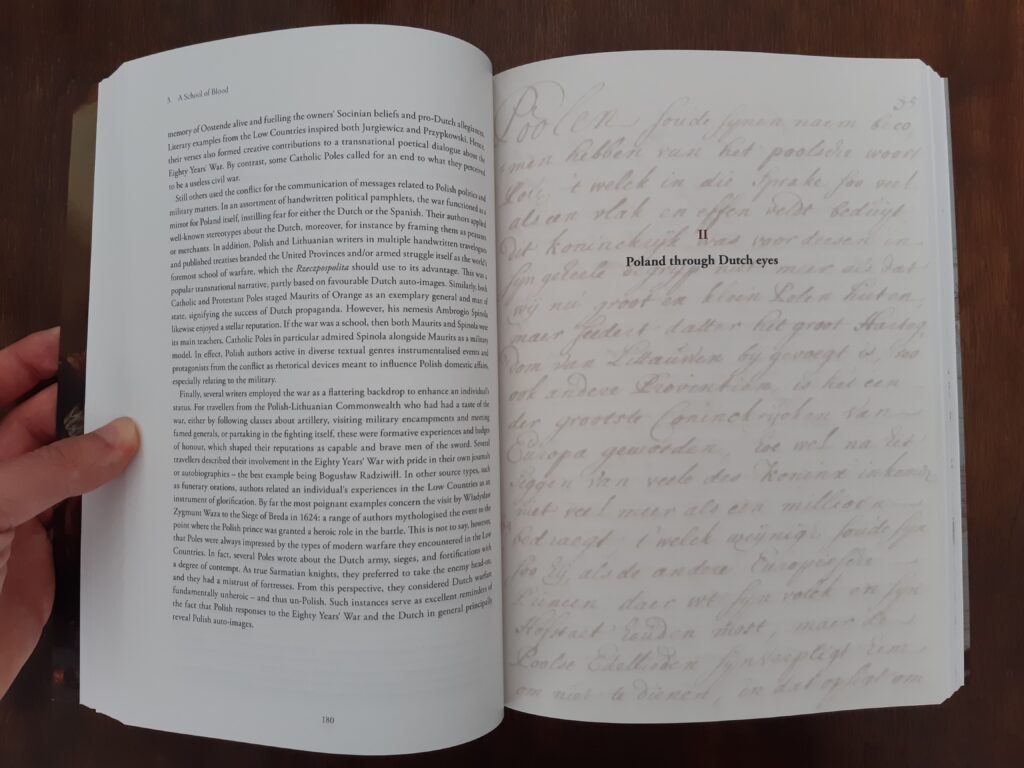

This is it: Heretical Heroes and Savage Saviours. The Dutch and Poles in each other’s imaginations during the long seventeenth century, the final version of my PhD thesis! Almost 600 pages and over 150 illustrations which together tell a story about how the Dutch and Poles imagined each other during the long seventeenth century, and how we can explain these representations. From the United Provinces as a natural and cultural marvel and school of warfare to the Dutch population as Calvinist, freedom-loving peasants, and from Poland as a grain-rich trading partner and champion of Christendom to the Poles themselves as northern savages and inhabitants of Europe’s Orient. The book will be available in Open Access after my defence on 24 October!

This is it: Heretical Heroes and Savage Saviours. The Dutch and Poles in each other’s imaginations during the long seventeenth century, the final version of my PhD thesis! Almost 600 pages and over 150 illustrations which together tell a story about how the Dutch and Poles imagined each other during the long seventeenth century, and how we can explain these representations. From the United Provinces as a natural and cultural marvel and school of warfare to the Dutch population as Calvinist, freedom-loving peasants, and from Poland as a grain-rich trading partner and champion of Christendom to the Poles themselves as northern savages and inhabitants of Europe’s Orient. The book will be available in Open Access after my defence on 24 October!

Hoekstra placed himself in that same 17th-century tradition by quoting the famed Dutch poet Joost van den Vondel, who praised Gdańsk in 1635 to boost the grain trade. Almost 400 years later, Vondel’s poem thus once again served to bolster Dutch-Polish relations. Also, Vondel’s definition of Gdańsk as “queen of the northern region” is a translation of a Latin verse about Gdańsk by the Polish poet Sarbiewski/Sarbievius, published in 1634. In other words: Hoekstra quoted Vondel quoting Sarbiewski. This is some serious intertextuality! Moreover, my own paper on early modern diplomacy has become part of the modern diplomatic process. And so have I: the fact that I’m a “Dutch historian” is especially relevant in this context (Hoekstra missed the opportunity to say that I’m also Polish, however).

Hoekstra placed himself in that same 17th-century tradition by quoting the famed Dutch poet Joost van den Vondel, who praised Gdańsk in 1635 to boost the grain trade. Almost 400 years later, Vondel’s poem thus once again served to bolster Dutch-Polish relations. Also, Vondel’s definition of Gdańsk as “queen of the northern region” is a translation of a Latin verse about Gdańsk by the Polish poet Sarbiewski/Sarbievius, published in 1634. In other words: Hoekstra quoted Vondel quoting Sarbiewski. This is some serious intertextuality! Moreover, my own paper on early modern diplomacy has become part of the modern diplomatic process. And so have I: the fact that I’m a “Dutch historian” is especially relevant in this context (Hoekstra missed the opportunity to say that I’m also Polish, however).