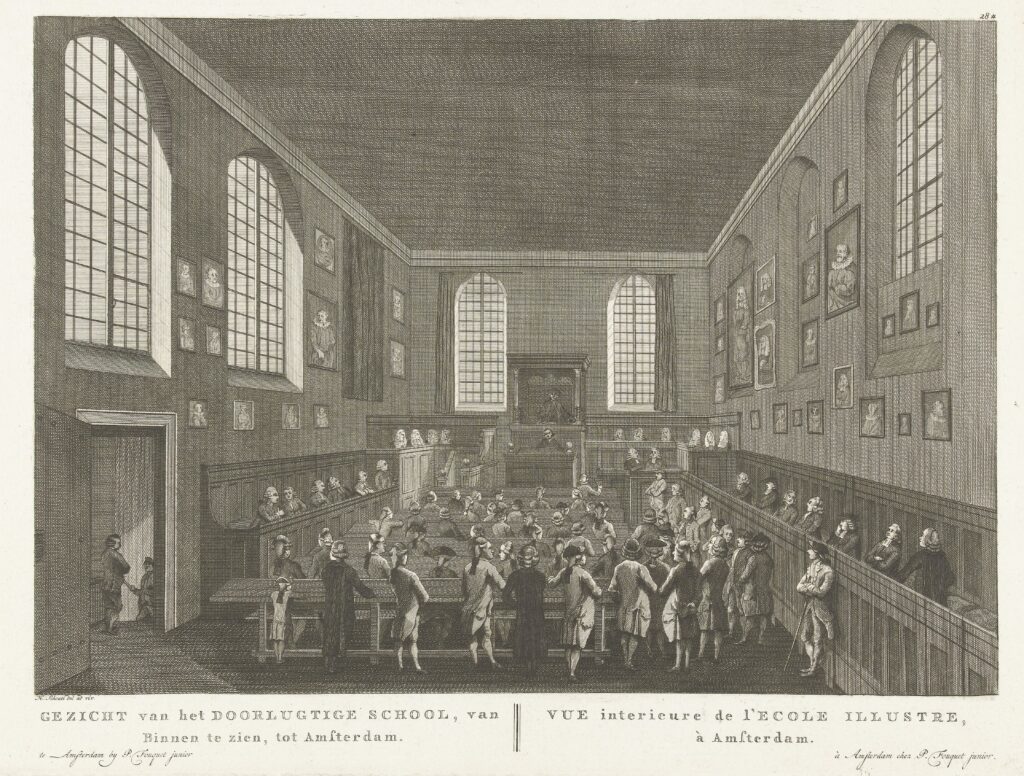

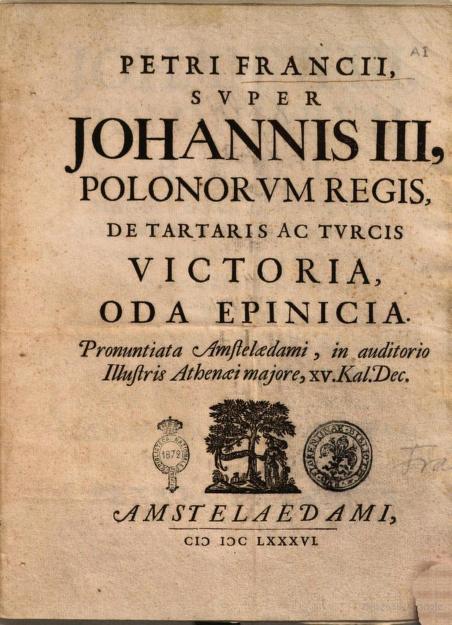

On this day in 1686, people in Amsterdam gathered to praise King Jan III Sobieski of Poland. In the city’s Athenaeum Illustre, the forerunner of the University of Amsterdam, the Dutch professor of ancient rhetoric Petrus Francius delivered a public reading of a poem he had written in Sobieski’s honour. The cause for this event was the Siege of Buda, which took place in the summer of 1686. The armies of the so-called Holy League at that time reclaimed the city of Buda, ending almost 150 years of Ottoman rule. Francius subsequently wrote four elaborate poems about the Holy League’s wars against the Ottomans, which he published and recited in the Athenaeum Illustre and the New Church of Amsterdam. Sobieski played no part in the Siege of Buda, but he had made a name for himself as a grand Christian champion, especially after his actions at the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

The poem by Francius is an overwhelming appraisal covering nineteen pages, which pulls out all the stops. The Polish king’s bravura and success on the battlefield is sensationally described and contrasted with the supposed shame and infamy of his enemies. Moreover, Francius compared Sobieski with mythological figures like Mars and Hercules, but also with historical rulers such as Charlemagne and Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. In addition, the Dutchman extolled Sobieski’s sons, Jakub and Aleksander. This part of the eulogy aligns with Sobieski’s contemporary propaganda, which after 1683 pushed his (failed) agenda of establishing a royal dynasty. The published version of the poem shows that Francius used various sources, including the words of a Polish diplomat who resided in Holland.

The poem by Francius is an overwhelming appraisal covering nineteen pages, which pulls out all the stops. The Polish king’s bravura and success on the battlefield is sensationally described and contrasted with the supposed shame and infamy of his enemies. Moreover, Francius compared Sobieski with mythological figures like Mars and Hercules, but also with historical rulers such as Charlemagne and Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. In addition, the Dutchman extolled Sobieski’s sons, Jakub and Aleksander. This part of the eulogy aligns with Sobieski’s contemporary propaganda, which after 1683 pushed his (failed) agenda of establishing a royal dynasty. The published version of the poem shows that Francius used various sources, including the words of a Polish diplomat who resided in Holland.

Most of the people in the Athenaeum Illustre that day must have been educated: the poem was written in Latin. One of them was Joan Pluimer, the director of the Amsterdam Schouwburg, who responded to Francius’s performance with a Dutch poem of his own. According to Pluimer, the entire audience stood in amazement:

Who would not stammer, stray, faced with the virtue of a god [Sobieski],

Besides only Francius? He portrays the war hero [Sobieski];

The high school [Athenaeum Illustre] then seems a bulwark in the field;

His eyes shoot lightning, while he thunders with words.

Learned and unlearned, all stand amazed,

And see nature and art in the highest form.

Furthermore, letters by and to Francius reveal that he sent his poem to other people who appreciated his work, both in the Dutch Republic and abroad. The composition may even have reached Poland: in early 1687, the aforementioned Polish diplomat sent an unspecified panegyric of Sobieski from Holland to Gdańsk. The Polish king was an avid book collector. Perhaps he read Francius’s poem himself?

The case of Francius is the most telling literary example of the fame Sobieski enjoyed in the Northern Netherlands: ever since his royal election in 1674, numerous Dutch artists, artisans and authors had celebrated Sobieski through prints, poems, pamphlets, theatre plays and other means. I briefly wrote about some of these instances here and here, and I have dedicated this article to the Dutch reception of Sobieski prior to his victory at Vienna. My PhD thesis offers even more elaborate information, and also discusses Dutch reactions to Sobieski after 1683, including the poems by Petrus Francius and Joan Pluimer.

*I originally wrote (a different version of) this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 48.