One of my favourite pastimes is to engage with younger generations about language and history. I could do so again yesterday, this time to talk about new research that I have only just completed, on Dutch-Polish bilingualism in the 17th century: who could speak Polish and Dutch at the time, where and why? My presentation included Dutch traders in Gdańsk, Polish students in Franeker and Leiden, and Jewish translators in Amsterdam. What made this event special was the fact that my audience itself was bilingual, as I was a guest at Fundacja Polskie Centrum Edukacji i Kultury Lokomotywa in Amsterdam, where I gave a talk about Dutch-Polish historical relations last year as well. Lokomotywa is a Saturday school for children of Polish descent (there are dozens of such schools in the Netherlands – I myself attended the Polish school in Goirle for many years). Talking to bilingual children about bilingualism: I was over the moon, and I think they liked it too, especially when we got to the quiz about old Polish and Dutch words!

Category Archives: Presentations

PhD Thesis Defended!

On 24 October, I successfully defended my PhD thesis entitled Heretical Heroes and Savage Saviours. The Dutch and Poles in each other’s imaginations during the long seventeenth century. I thoroughly enjoyed the ceremony and subsequent celebrations: a reception, dinner and party with family and friends! My thanks go out to all those who made the day’s festivities possible, especially my supervisors prof. dr. Lotte Jensen and prof. dr. Johan Oosterman, the members of the manuscript committee, and my paranymphs dr. Lieke Verheijen-van Wijk and dr. Alan Moss.

My PhD thesis can be downloaded for free here. Interested in a summary? This video shows a recording of the brief presentation I gave at the start of the defence ceremony (in Dutch).

Lezing in Nijmegen: Tweetaligheid, Poëzie en Diplomatie in de 17e eeuw

Momenteel vindt het 21e Colloquium Neerlandicum plaats: een groot, internationaal congres van en voor neerlandici uit de hele wereld, georganiseerd door de IVN (Internationale Vereniging voor Neerlandistiek). Dit jaar is het congres neergestreken in de Radboud Universiteit in Nijmegen. Ik verzorgde er een lezing over een onderdeel van mijn promotieonderzoek.

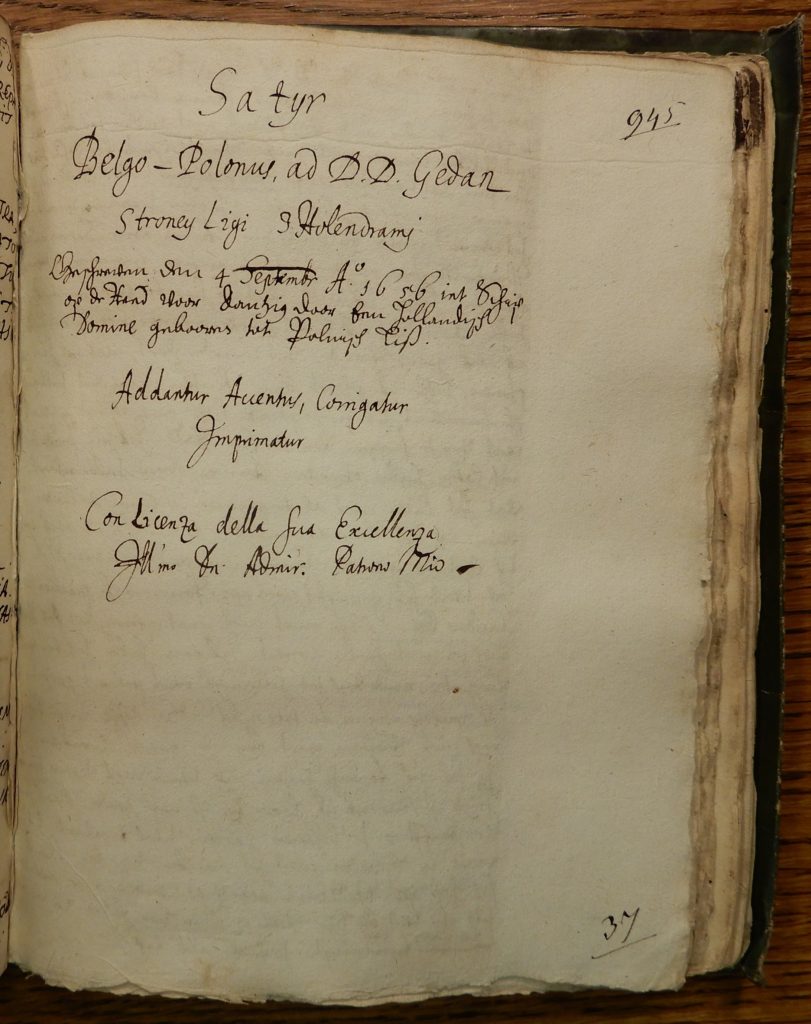

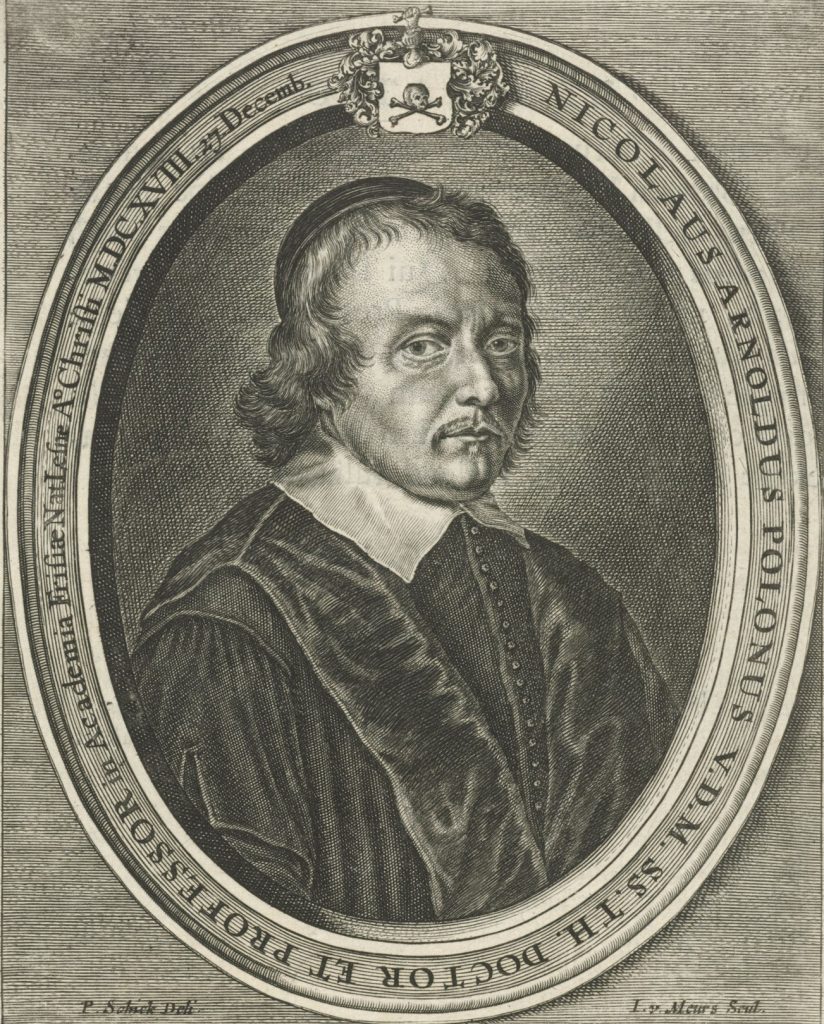

Mijn lezing ging over de Satyr Belgo-Polonus (Nederlands-Poolse Sater): een tot nog toe niet onderzocht, handgeschreven gedicht uit 1656, dat ik een aantal jaar geleden vond in het archief in Gdańsk. Het gedicht is geschreven door Nicolaus Arnoldus, een uit het Poolse Leszno afkomstige calvinist die werkte als predikant en hoogleraar theologie in Franeker. In 1656 nam hij deel aan een diplomatieke missie naar Polen, die o.a. tot doel had een verdrag tot stand te brengen tussen de Republiek en de Baltische havenstad Gdańsk, die hoorde bij het Koninkrijk Polen, maar ook veel vrijheden genoot. Dat verdrag stipuleerde bijvoorbeeld dat de Republiek militaire en financiële hulp zou bieden aan Gdańsk, maar voorzag er ook in dat Nederlandse handelaren aldaar evenveel rechten zouden krijgen als de lokale kooplieden zelf. Daarnaast zou de stad neutraal moeten worden in de oorlog tussen Zweden en Polen, die op dat moment gaande was. In 1655 waren de Zweden namelijk Polen binnengevallen, wat negatieve gevolgen had voor de Nederlandse graanhandel met Gdańsk. De situatie leek nog erger te worden toen de Zweden dreigden Gdańsk in te nemen. Arnoldus moet zijn meegestuurd op de missie vanwege zijn kennis van de Poolse taal en cultuur.

De titelpagina van het gedicht vermeldt dat de tekst in september 1656 op een schip voor Gdańsk is geschreven “door een Hollandisch Domine gebooren tot Polnisch Liss [Leszno]”. Die aanduiding wijst op Arnoldus. Het Poolse gedicht wordt voorafgegaan door een voorwoord in het Nederlands, waarin de auteur bescheiden stelt geen van beide talen goed te beheersen: “van alles kan ik een beetje, maar niks beheers ik volledig”. Bovendien maakt het voorwoord duidelijk dat Arnoldus betaald kreeg door een Nederlandse “admiraal” – vermoedelijk een van de scheepsvoogden die een paar maanden daarvoor met een vloot naar Gdańsk waren gevaren. Met andere woorden: Arnoldus handelde onder patronage van de Nederlanders.

De titelpagina van het gedicht vermeldt dat de tekst in september 1656 op een schip voor Gdańsk is geschreven “door een Hollandisch Domine gebooren tot Polnisch Liss [Leszno]”. Die aanduiding wijst op Arnoldus. Het Poolse gedicht wordt voorafgegaan door een voorwoord in het Nederlands, waarin de auteur bescheiden stelt geen van beide talen goed te beheersen: “van alles kan ik een beetje, maar niks beheers ik volledig”. Bovendien maakt het voorwoord duidelijk dat Arnoldus betaald kreeg door een Nederlandse “admiraal” – vermoedelijk een van de scheepsvoogden die een paar maanden daarvoor met een vloot naar Gdańsk waren gevaren. Met andere woorden: Arnoldus handelde onder patronage van de Nederlanders.

Het gedicht zelf beslaat ruim negen pagina’s en probeert de Pools lezende autoriteiten in Gdańsk ervan te overtuigen het verdrag te ondertekenen. Daarvoor gebruikt de auteur allerhande argumenten, bijvoorbeeld dat de Nederlanders competente en betrouwbare partners zijn, die steun krijgen van God. Belangrijk is ook dat het gedicht aansluit bij zogenaamde “satirische” Poolse poëzie, een genre dat destijds redelijk populair was en teruggreep op een werk van de immens invloedrijke 16-eeuwse dichter Jan Kochanowski.

Doorgaans spreekt in “satirische” gedichten een sater (een mythologisch wezen dat half-mens, half-bok is) een monoloog uit, waarin hij commentaar levert op de Poolse maatschappij. Als halve buitenstaander heeft hij enige afstand tot de realiteit, maar hij bezit ook kennis van Polen en haar inwoners. Vandaar dat Arnoldus zich afficheerde als “Nederlands-Poolse Sater”: als dominee en hoogleraar in Franeker was hij voor de Polen een buitenstaander, maar vanwege zijn Poolse afkomst en kennis van het Pools achtte hij zich goed in staat advies te geven aan Gdańsk. De lokale lezers zullen bovendien direct hebben herkend dat het gedicht aanhaakte bij het genre van de “satirische” poëzie – iets wat sympathie kan hebben gewekt.

Helaas voor Arnoldus en de Nederlanders had zijn gedicht echter niet het gewenste effect: het verdrag kwam er niet. Gdańsk wilde trouw blijven aan de Poolse koning en was niet van zins om extra rechten te geven aan Nederlandse handelaren. Misschien is het gedicht van Arnoldus overigens niet eens gedrukt. De enige bekende versie is te vinden in een enorme collectie handgeschreven gedichten over allerhande internationale thema’s, die destijds werden verzameld en gekopieerd door een inwoner van Gdańsk. Van een diplomatiek instrument verwerden Arnoldus’ verzen zodoende tot een dichterlijk spoor van de actualiteit, vermoedelijk bedoeld ter lering en vermaak. Toch biedt de tekst een fascinerende en tot nog toe onbekende case study van zeventiende-eeuwse tweetaligheid, de verwevenheid tussen poëzie en diplomatie in vroegmodern Europa, en de complexe geschiedenis van Pools-Nederlandse relaties.

In mijn proefschrift ga ik nader in op de inhoud van de Satyr Belgo-Polonus. Na de afronding van mijn dissertatie ben ik van plan er een artikel over te schrijven, inclusief een becommentarieerde uitgave en vertaling van het gedicht.

KNHG lezing: Gedichten uit Gdańsk over het Rampjaar

Op 22 april vond het jaarlijkse KNHG Voorjaarscongres plaats in het BHIC (Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum) te ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Het congres had als titel ‘Bloed, kruit en tranen: Betekenis en herdenking van het Rampjaar 1672’ en werd georganiseerd ter gelegenheid van 350 jaar Rampjaar. Historici, erfgoedprofessionals, museummedewerkers, onderwijzers en andere geïnteresseerden kwamen bijeen om te praten over verschillende aspecten van het jaar 1672. Ter sprake kwamen o.a. onderbelichte perspectieven uit binnen- en buitenland, de herinneringscultuur vandaag de dag, en zelfs de geur van het Rampjaar.

Ikzelf verzorgde een lezing in de sessie ‘Het Rampjaar in woord en beeld: Reacties en representaties uit de Republiek, Gdańsk en Aleppo’. Mijn presentatie droeg de titel ‘Baltische betrokkenheid tussen schrik en scherts: Gedichten uit Gdańsk over het Rampjaar’.

De gebeurtenissen van het Rampjaar trokken internationaal de aandacht. Zo ook in de Baltische havenstad Gdańsk (Danzig), waar ik gedurende mijn promotieonderzoek zeker 10-15 gedichten heb kunnen vinden die reageren op de rampspoed die de Republiek in 1672 ten deel viel. Uiteindelijk heb ik om meerdere redenen besloten om het bronmateriaal uit Gdańsk grotendeels uit mijn proefschrift te laten en te bewaren voor een toekomstig onderzoeksproject. Met mijn lezing liet ik zien wat de mogelijkheden zijn van een dergelijk onderzoek. Mijn doel was om te achterhalen wat de gedichten ons kunnen leren over de vraag hoe en waarom men in Gdańsk het Rampjaar beleefde. De meeste gedichten zijn geschreven in het Latijn en zijn te vinden in zogenaamde sylvae: grote poëzieverzamelingen met verzen over allerhande internationale onderwerpen. Ze laten grofweg drie perspectieven zien: pro-De Witt, anti-de Witt en meer algemeen pro-Republiek. Van al die perspectieven besprak ik één voorbeeld.

Wellicht het meest bijzondere gedicht is een werk van de plaatselijke docent en geleerde Johannes Petrus Titius (1619-1689), die een gloedvol grafschrift schreef voor de gebroeders De Witt. Zijn gedicht is uitgesproken positief over de broers, spreekt vol walging over hun tragische dood en bevat een algemene les voor de lezers: pas op voor het wisselvallige lot! Een gedrukt pamflet met zijn Latijnse gedicht – inclusief Duitse vertaling en portretten van Johan en Cornelis de Witt – was reeds bekend, maar de auteur en plaats van uitgave nog niet. Aangezien ik in Gdańsk twee handschreven, gesigneerde kopieën van het gedicht heb kunnen vinden, is het aannemelijk dat Titius voor de compositie verantwoordelijk was en het pamflet in Gdańsk werd gepubliceerd. Kennelijk waren meerdere mensen ter plekke bereid om tijd en geld te investeren in de verspreiding van dit pro-De Witt geluid.

Van de meeste andere gedichten heb ik kunnen achterhalen dat ze kopieën zijn van elders gedrukte teksten, met name afkomstig uit de Republiek. Tussen Gdańsk en de Noordelijke Nederlanden bestond veel verkeer van mensen en goederen, dus is het niet verwonderlijk dat ook nieuws en literatuur van de Republiek naar de Baltische havenstad reisde. Tussen de anti-De Witt gedichten zit o.a. een lang, anoniem Nederlands grafschrift van Johan de Witt, dat oorspronkelijk gedrukt was in de Republiek. Het bevestigt het idee dat velen in Gdańsk het Nederlands machtig waren – al heeft de kopiist de tekst her en der ‘verduitst’, bijvoorbeeld door naamvallen aan te passen. Interessant is ook dat zowel pro- als anti-De Witt gedichten soms in één en hetzelfde manuscript te vinden zijn: dat men een gedicht kopieerde, betekent dus niet per definitie dat men het eens was met het sentiment dat het gedicht vertolkt. Helder is in ieder geval wel dat de retorische en ideologische strijd die in de Republiek woedde tussen de staats- en prinsgezinden ook actief werd gevoerd in Gdańsk.

Ik eindigde door te speculeren over de mogelijke redenen die men in Gdańsk kon hebben om gedichten te schrijven en verspreiden over het Rampjaar. Ten eerste benoemde ik een spanningsveld tussen persoonlijke en ‘gemaakte’ motivatie: iemand kon oprechte betrokkenheid voelen bij de gebeurtenissen van 1672, maar kon ook betaald worden om gedichten (over) te schrijven, bijvoorbeeld door de autoriteiten van Gdańsk. Daarnaast is er een spanningsveld tussen plaatselijk en transnationaal belang: auteurs of kopiisten konden bijvoorbeeld schrijven om de publieke opinie te beïnvloeden in zowel binnen- als buitenland. Sommige gedichten bevatten immers boodschappen die ook lokaal belangwekkend zullen zijn geweest, omdat ze betrekking hebben op correct staatsbestuur of religieuze tolerantie. Tot slot was er wellicht sprake van literair gemotiveerde interesse: mensen genoten ervan om gedichten te schrijven en te lezen, en een goedgevulde sylva kon dienen als een dichterlijk archief van de actualiteit, waarin allerhande, ook tegenstrijdige geluiden konden worden samengebracht.

Mijn lezing wierp zodoende licht op zowel de inhoud als de wordingsgeschiedenis van de contemporaine, internationale verbeelding van het Rampjaar, dat klaarblijkelijk bijzonder de aandacht trok in Gdańsk. Ik hoop mijn onderzoek over de literaire banden tussen de Republiek en Gdańsk ooit verder te kunnen uitwerken: de archieven in Gdańsk liggen vol met tot dusverre onbekende gedichten en prozateksten, die een belangrijke literaire dimensie vormden van de culturele verwevenheid tussen de Baltische havenstad en de Noordelijke Nederlanden. Deze kant van de betrekkingen tussen vroegmodern Polen en Nederland verdient meer aandacht in de toekomst.

Familiar Foreigners: Paper at the Huizinga PhD Conference

On 13 October, I presented a paper at the yearly Huizinga conference for PhD candidates. Due to the pandemic, the conference was held entirely online. My paper was entitled Familiar Foreigners. Poles through Dutch Eyes in the Seventeenth Century.

I discussed work in progress on the different ways in which the Dutch during the seventeenth century imagined the Polish people. Firstly, I analysed a variety of Dutch visualisations of ‘Poles’ and ‘Polishness’, ranging from engravings to gable stones and from paintings to ‘Polish’ stage costumes. While such representations were partly based on reality, a comparison with Dutch portraits of real Poles shows how these could break the mould. For whereas a Pole’s appearance was typically associated with the exoticism of the orient, and hardly differed from his Hungarian, Russian, or even Turkish counterparts, depictions of individuals could deviate from this pattern, as Poles navigated between ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ guises.

Secondly, I used several poems, travel accounts, and other sources to reconstruct the ways in which Dutch authors imagined Polish characters and customs. Typical Poles were identified as Sarmatians, a bellicose, brutal, and barbaric people, whose backward nature was shaped by the cold climate and severe living conditions of their homeland. However, these negative notions are challenged by several other sources, mainly Latin poems by Dutch authors in honour of their Polish friends. These compositions reveal that, despite the stereotypes, Dutch poets maintained and celebrated warm relations with Polish individuals in a variety of contexts, from scholarship to warfare to religion. Together, the visual and textual source material demonstrates that, through seventeenth-century Dutch eyes, Poles were familiar foreigners.

At the Warsaw Institute of History

From 2 to 15 December, I am a guest researcher at The Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, which is located at the city’s Old Town Market Square. Besides doing research in Warsaw’s archives and libraries, I gave a presentation for members of the institute, entitled Polski Herkules: Północno-niderlandzka recepcja Jana III Sobieskiego w późnym siedemnastym wieku (The Polish Hercules: The reception of John III Sobieski in the Northern Netherlands during the late seventeenth century). I discussed the international importance of a series of prints made for the Polish king by the Dutch engraver Romeyn de Hooghe after Sobieski’s election in 1674, as well as the main characteristics of the wide range of poems and prints produced in the Northern Netherlands following his victory at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. The comments and questions I received were extremely helpful! My research stay is funded by an Erasmus+ scholarship.

From 2 to 15 December, I am a guest researcher at The Tadeusz Manteuffel Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, which is located at the city’s Old Town Market Square. Besides doing research in Warsaw’s archives and libraries, I gave a presentation for members of the institute, entitled Polski Herkules: Północno-niderlandzka recepcja Jana III Sobieskiego w późnym siedemnastym wieku (The Polish Hercules: The reception of John III Sobieski in the Northern Netherlands during the late seventeenth century). I discussed the international importance of a series of prints made for the Polish king by the Dutch engraver Romeyn de Hooghe after Sobieski’s election in 1674, as well as the main characteristics of the wide range of poems and prints produced in the Northern Netherlands following his victory at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. The comments and questions I received were extremely helpful! My research stay is funded by an Erasmus+ scholarship.

Peripheral Polish Prussia?

On 15 November, I gave a paper presentation at Radboud University’s international conference Is Europe Inclusive? Together with prof. dr. Marguérite Corporaal, I organised a panel on conceptions of European centres and peripheries throughout the ages. In my paper, entitled Peripheral Polish Prussia? Contrasting Dutch Perceptions of Prussia and the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth during the seventeenth century, I argued that notions of centres and peripheries are ever changing and dependent on the observer. I used the case of Prussia, which during the nineteenth century was framed as the centre of Germanness, but which nowadays no longer exists as a geographic entity.

In my presentation, I posed the question how Prussia was perceived before its rise to power as an independent state, when during the seventeenth century it was under Polish rule. Royal Prussia, with Danzig as its most important port, was an integral part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1772, while Ducal Prussia was a vassal of the Polish king from 1525 until 1660. The observers I chose, the Dutch, had strong economic and cultural ties with Prussia. Did the Dutch view Prussia, which was culturally similar to the Low Countries and of great economic importance to the Dutch Republic, as a centre, or rather as a periphery and a mere province within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth?

Using a variety of sources, I made clear that the Dutch had differing opinions about the region: while some sources preferred Prussia to Poland proper, saying that Prussian houses and grain were superior to Poland’s, other sources paint a different picture. Abraham Booth, who wrote the first Dutch eyewitness account of Poland-Lithuania, printed in Amsterdam in 1632, wrote an unflattering report of his journey through both Prussia and Poland. Negative elements were, for example, vast forests, cruel Polish soldiers, bad roads and shabby accommodations. This presentation is hardly surprising, as Booth wrote his account during a diplomatic mission to Prussia, in which the Dutch mediated between the Swedes and Poles after the Swedes had invaded Polish territory. The Dutch were officially allied with the Swedes, however. On the other hand, Poland and Prussia always feature favourably in the works of Joost van den Vondel, the most prominent Dutch poet of the seventeenth century. Vondel saw Prussia as belonging to Poland, and repeatedly praised the Commonwealth for its fertility and the role it played as a bulwark of Christendom. This no doubt had to do with Vondel’s Catholic sympathies. In this way, I hope to have shown that what constitutes a centre or a periphery is not fixed and easily measurable, but rather depends on the historical context and background of the observer.

Scholarly Identity on the Grand Tour: Paper Presentation in Utrecht

On 7 November, Alan Moss and I gave a paper presentation in Utrecht, at an international conference entitled Memory and Identity in the Learned World: Community Formation in the Early Modern World of Science and Learning. The conference was organised by the members of the ERC-funded SKILLNET project. Our paper was entitled The Graves of Learned Men: Scholarly Identity on the Dutch and Polish Grand Tour, and discussed the ways in which seventeenth-century Dutch and Polish travellers gave expression to a scholarly identity by reflecting on so-called lieux de savoir, places of knowledge. While journeying through Europe, travellers would often visit such places and describe them in their travelogues. Popular destinations were the universities at Oxford, Leiden and Leuven, and so were the graves, birth places and statues of learned men like Erasmus, Lipsius, Grotius or the Scaligers. Some of these scholars also left behind ‘relics’, like a pen, a last will or even a skull. Alan and I gave various examples of Poles and Dutchmen describing such lieux de savoir, including the Dutch poet Caspar van Kinschot (1622-1649), who wrote several Latin compositions when visiting the house of the Scaligers in Agen.

Moving Humanities Conference at Radboud University: Finding Meaning

On 24 October, humanities scholars gathered at Radboud University for the biennial Moving Humanities conference. PhD candidates and Research Master students from various humanities disciplines gave presentations on a topic important to all: finding meaning, be it in a specific source, sound or word, a historical development, or humanities research for society itself. Keynote speeches were given by prof. dr. Leonie Cornips, who spoke about the language of cows, and by prof. dr. Bas Haring, who shared his thoughts on how humanities research and the natural sciences can fruitfully engage with each other. The conference was funded by the Radboud Graduate School for the Humanities and was organised by Merijn Beeksma, Marc Colsen, Marieke van Egeraat, Aurélia Nana Gassa Gonga, Tara Struik and myself.

Paper op Historicidagen: Een Ander Europa

Tijdens de Historicidagen, die dit jaar van 22 t/m 24 augustus werden georganiseerd in Groningen, heb ik een paper gepresenteerd met als titel Een Ander Europa: De scheiding tussen Oost en West voorbij. Het thema van het congres was ‘inclusieve geschiedenis’. In mijn presentatie legde ik daarom uit waar de mentale scheiding tussen West- en Oost-Europa vandaan komt, hoe die ook nu nog wordt bestendigd en wat wij daar als historici aan kunnen doen, om zodoende tot een meer inclusieve geschiedenis van heel Europa te komen. Eén van de manieren: heb het in publicaties over de tijd vóór de Verlichting niet over ‘West-‘ of ‘Oost-Europa’, want die concepten ontstonden pas in de achttiende eeuw.

Tijdens de Historicidagen, die dit jaar van 22 t/m 24 augustus werden georganiseerd in Groningen, heb ik een paper gepresenteerd met als titel Een Ander Europa: De scheiding tussen Oost en West voorbij. Het thema van het congres was ‘inclusieve geschiedenis’. In mijn presentatie legde ik daarom uit waar de mentale scheiding tussen West- en Oost-Europa vandaan komt, hoe die ook nu nog wordt bestendigd en wat wij daar als historici aan kunnen doen, om zodoende tot een meer inclusieve geschiedenis van heel Europa te komen. Eén van de manieren: heb het in publicaties over de tijd vóór de Verlichting niet over ‘West-‘ of ‘Oost-Europa’, want die concepten ontstonden pas in de achttiende eeuw.