On 31 July 1667, the Second Anglo-Dutch War was concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda. Two years of naval warfare resulted in a Dutch victory. In the Republic, celebrations included fireworks and festivals, and numerous poets eulogised their country’s achievement.

Yet the peace was not only celebrated within the Dutch Republic. In Gdańsk (or Danzig, if you will), I found two Latin poems relating to the Treaty of Breda. Why were the authors interested in this topic, what did they write about it, and what did they hope to achieve?

International Gdańsk

Occasional poetry was a common phenomenon in Early Modern Europe, and Gdańsk was no exception. Its poets produced countless compositions, for example applauding the Polish king’s victories, celebrating newly wedded couples, or honouring the deceased.

Still, one might wonder why poets from Gdańsk, a Baltic port situated in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, would care about the goings-on of a war fought between the Dutch and English. The answer lies in the fact that Gdańsk was a highly cosmopolitan city and a thriving hub of international trade, inhabited by Poles, Germans, Jews, Scandinavians, Dutchmen, Englishmen, Scotsmen and many others. The Polish Academy of Sciences Library in Gdańsk houses a wealth of occasional poetry discussing all sorts of European topics, such as the deaths of monarchs (for example those of Philip IV of Spain, Charles I or Gustav II Adolph), royal marriages (for example between William II of Orange and Mary Henrietta Stuart), or the many wars fought on the continent. Due to the particularly strong economic, cultural and diplomatic ties between the city and the Dutch Republic, a relatively high number of poems has a ‘Dutch flavour’. For example, I found Latin compositions in honour of the poetess Anna Maria van Schurman, the admirals Michiel de Ruyter and Jacob van Wassenaar Obdam, and the De Witt brothers. The two compositions relating to the Treaty of Breda thus fit into a far broader context of internationally oriented Gdańsk poetry.

“Eternal laurel wreaths”

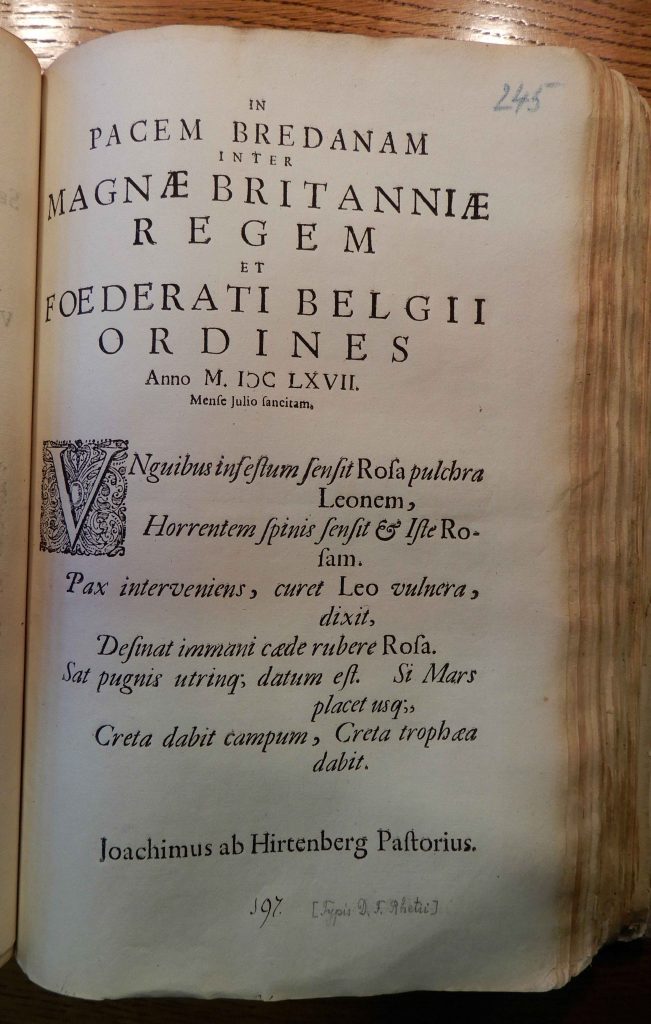

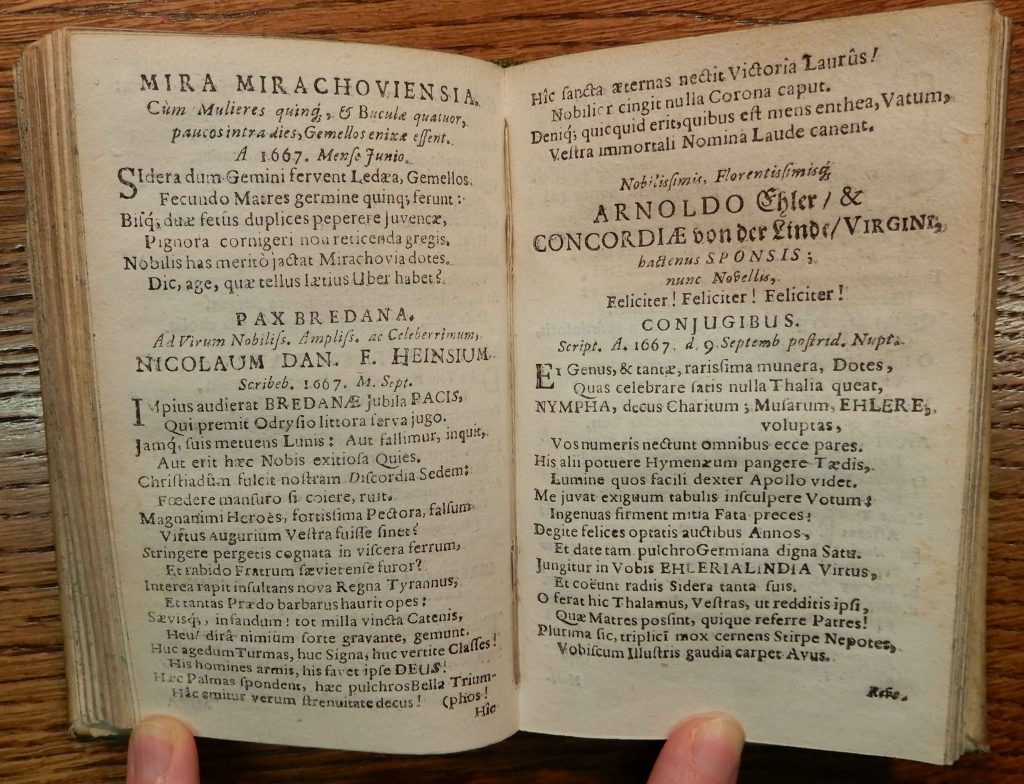

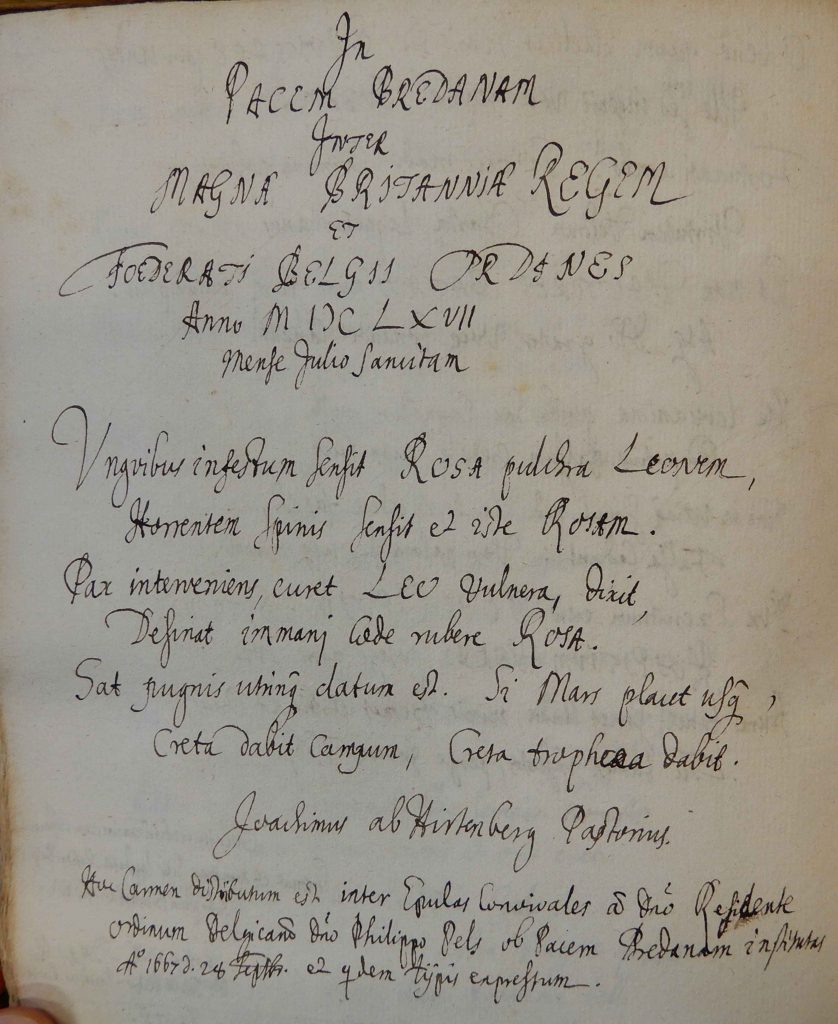

The poems were written by two of the most prolific authors of the city: Joachim Pastorius (1611-1681) and Johannes Petrus Titius (1619-1689), both born Silesians who settled in Gdańsk and went on to have impressive scholarly and literary careers (both were professors at the city’s Gymnasium Academicum, for example). Pastorius’s poem is preserved in two versions: one printed as a pamphlet and one preserved in a large handwritten collection of Latin, German and Polish poetry. Titius’s poem I found in an edition of his poetical oeuvre, printed in Gdańsk in 1670. It was probably circulated as a pamphlet as well – the title says that it was written in September 1667 –, but I have not found any such copy.

While the Dutch responses to the end of the war generally celebrate the newfound peace and applaud the Dutch regents or war heroes, Pastorius and Titius treat ‘Breda’ as an opportunity to start a new war: against the Turks. In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which battled the Ottoman Empire on multiple occasions, the conflict with the country’s southern neighbour formed a popular theme among many poets. Furthermore, a new Polish-Ottoman struggle had in 1666 broken out over the Ukraine, making it a ‘hot topic’ once more. More importantly, however, 1667 saw the final stages of the Cretan War, fought between the Turks and Venetians since 1645, and also involving, for example, the Papal States and France. According to Pastorius and Titius, the peace between the Dutch and English meant that the Christian forces could unite against the common foe.

Pastorius’s short composition ends with the subtle suggestion that the ‘Lion’ (the Dutch) and the ‘Rose’ (the English) continue fighting somewhere (and someone) else:

The beautiful Rose has felt the Lion, threatening with its claws,

And the Lion has felt the Rose, sharp because of its thorns.

When Peace intervened, it said: let the Lion lick his wounds,

Let the Rose stop this immense red slaughter.

Both sides have seen enough fighting; if Mars still pleases you,

Crete will provide a battlefield, Crete will provide trophies.

Titius’s poem is much longer, but much less subtle: according to him, the Ottoman “Crescent Moon” shuddered when receiving word of the Treaty of Breda, because its “Christian seat” thrived during Europe’s disunity. Peace between the English and the Dutch now means that the “Tirant”, who “gobbles up kingdoms” like “a barbarian thief”, must fear for his life. Titius appears to address the whole of Europe, trying to convince its leaders to reap eternal glory in the struggle against the Turks:

That is where you must send your troops, your battle flags, your fleets!

The people support these weapons, God himself supports them!

These wars promise palm branches, and beautiful trophies!

Through this effort, true virtue is procured!

Here, a sacred victory binds eternal laurel wreaths!

No head wears a nobler crown.

Sending a message

What did Pastorius and Titius hope to achieve by their poems? Did they really think that the Dutch and English would be swayed to fight the Turks? It is not unthinkable. In the handwritten version of Pastorius’s composition, a sentence is added, informing us that the poem was handed out during a festive banquet organised in Gdańsk on 28 September by the Dutch diplomat Philips Pels (1623-1682), in order to celebrate the Treaty of Breda. As the Republic’s official resident, Pels answered to the States-General. It is possible, therefore, that someone (Pastorius himself, perhaps, or some other prominent resident of the city) tried to influence the Dutch through the poem. Something similar is at work in Titius’s case: according to its title, the composition was dedicated to Nicolaas Heinsius (1620-1681), the famous Dutch poet and scholar. Both texts may thus have travelled to the Northern Netherlands. Whether they had an English audience, I do not know, but it seems evident that they were primarily intended for a Dutch readership – aside from the people of Gdańsk themselves. At the very least, the poems were meant to gain Dutch support against the heathen enemy, and to create a sense of Christian unity.

Perhaps more important, however, is the broader context of occasional poetry I discussed earlier. Through their poems, Pastorius and Titius assured that they were part of the intellectual life of Gdańsk, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and even Christian Europe as a whole. Indeed, we might say that they entered a poetical dialogue with other authors who supported the anti-Turkish cause. For example, Joost van den Vondel (1587-1679), the most prominent seventeenth-century poet of the Northern Netherlands, had in 1649 written a eulogy of a Venetian victory over the Turks, in which several Dutch vessels had also taken part (nota bene, Pastorius and Titius probably read Dutch). What is more, by tying into international events such as the Treaty of Breda, Pastorius and Titius strengthened their city’s and their country’s place on both the cultural and political stage of Europe.

To me personally, the poems are a testament to the rich and fascinating literary production of Gdańsk and Poland-Lithuania, so often forgotten by Western scholarship.