On 3 May, Poland celebrates the Constitution of 1791: the first constitution in European history, and second only to the Constitution of the United States of America, in force since 1789. The Polish Constitution was introduced during the Great Sejm of 1788-1792, and aimed to profoundly reform the political system of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. For example, it combined a constitutional monarchy with a division of executive, legislative and judicial powers (the trias politica), while also introducing political equality between the nobility and townspeople (serfs were not granted personal freedom, but placed under the protection of the government). Also, it banned the nobility’s right of liberum veto, which had led to corruption and the weakening of the Polish-Lithuanian state. King Stanisław August Poniatowski was one of the reforms’ main advocates.

Support for the new Polish Constitution also came from the Netherlands: two citizens of Amsterdam, called Gülcher and Mulder, sent a golden medal to the Polish king via the Warsaw-based banker Piotr Blank. Gülcher and Mulder were bankers as well, who lent significant amounts of money to the Polish court. They had a commercial interest in praising the king, therefore, but they may also have been driven by ideology: Gülcher was a patriot, who believed in the new ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity. A Polish newspaper from 2 August 1791 includes a transcript of a letter by Gülcher and Mulder to Poniatowski, which begins as follows: “Most illustrious king! Seized by admiration, together with the whole of Europe, for the revolution which Your Majesty and the Polish Sejm have accomplished, as fortuitous as it is beneficent, we have sought to find a way through which to immortalize this great event.”

Their solution was to employ the services of the famed medalist Johan Georg Holtzey, mint master in Amsterdam and Utrecht. One side of the medal shows a portrait of Poniatowski wearing a wreath of oak leaves: a symbol of civic merit. The Latin text not only addresses him as the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, but also as Patriae Parens: Father of the Fatherland. The other side of the medal features the royal coat of arms and various symbols of freedom, justice and religious tolerance. The inscription reads Terrore Libera: Free of Fear. No doubt, Poniatowski was glad to receive this idolizing Dutch token of solidarity.

Sadly, the reforms were short-lived: conservative Polish nobles conspired to have the Constitution abolished and sought the help of Empress Catherine of Russia, who quickly invaded the Commonwealth in order to maintain control over her western neighbor, which she saw as her protectorate. In 1793, the Constitution was annulled and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was partitioned for the second time.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 53.

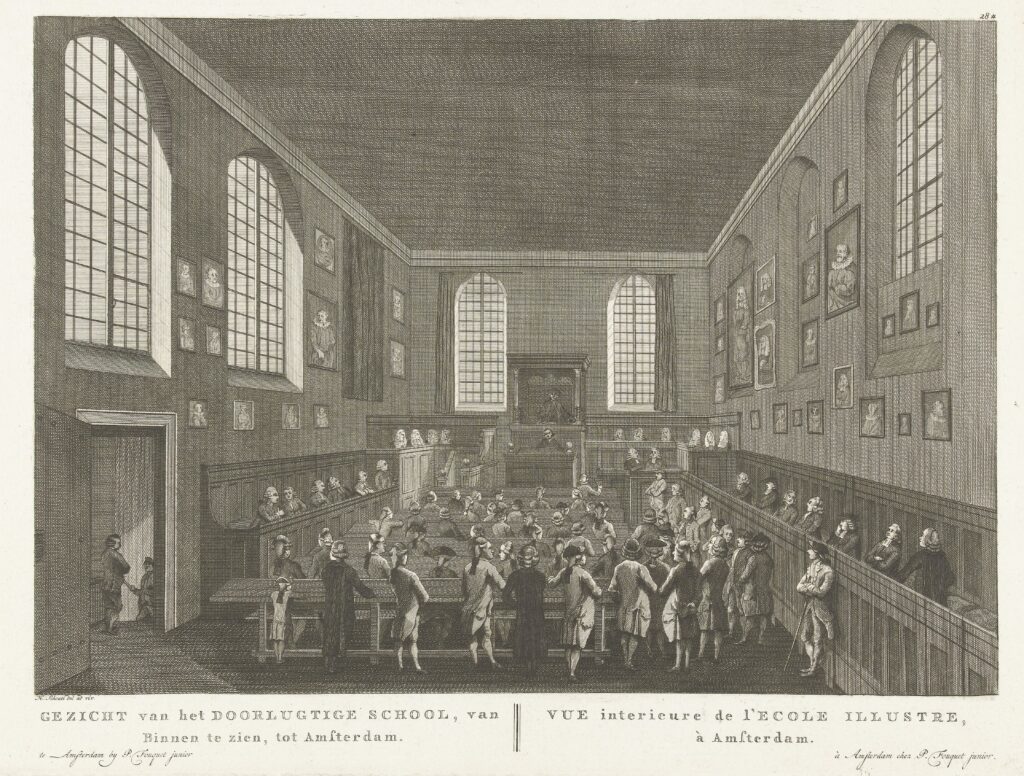

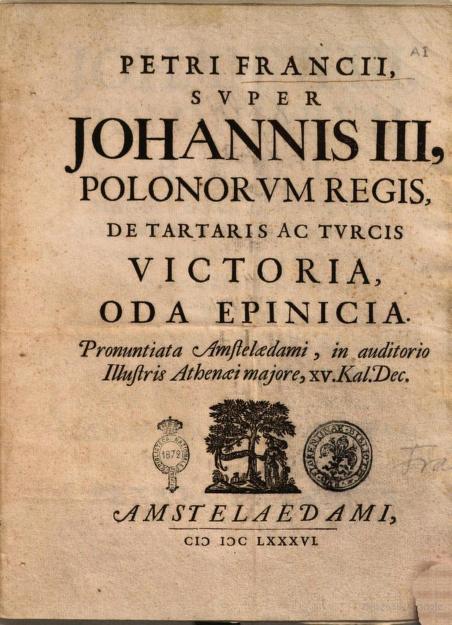

The poem by Francius is an overwhelming appraisal covering nineteen pages, which pulls out all the stops. The Polish king’s bravura and success on the battlefield is sensationally described and contrasted with the supposed shame and infamy of his enemies. Moreover, Francius compared Sobieski with mythological figures like Mars and Hercules, but also with historical rulers such as Charlemagne and Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. In addition, the Dutchman extolled Sobieski’s sons, Jakub and Aleksander. This part of the eulogy aligns with Sobieski’s contemporary propaganda, which after 1683 pushed his (failed) agenda of establishing a royal dynasty. The published version of the poem shows that Francius used various sources, including the words of a Polish diplomat who resided in Holland.

The poem by Francius is an overwhelming appraisal covering nineteen pages, which pulls out all the stops. The Polish king’s bravura and success on the battlefield is sensationally described and contrasted with the supposed shame and infamy of his enemies. Moreover, Francius compared Sobieski with mythological figures like Mars and Hercules, but also with historical rulers such as Charlemagne and Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. In addition, the Dutchman extolled Sobieski’s sons, Jakub and Aleksander. This part of the eulogy aligns with Sobieski’s contemporary propaganda, which after 1683 pushed his (failed) agenda of establishing a royal dynasty. The published version of the poem shows that Francius used various sources, including the words of a Polish diplomat who resided in Holland.