Now that travelling has become more difficult due to the global pandemic, we may resort to books as a means to make mental journeys to other countries, for example to Poland. The first Dutchman to write a published account of his voyage through Poland was Joris van der Does/Georgius Dousa (1574-1599), who was the son of an acclaimed Dutch scholar. The young Joris passed through Poland in the 1590s during an educational journey to Constantinople. In 1599, a Latin description of his travels was published in Leiden, which was partially translated into Dutch and issued in Dordrecht in 1652.

Joris’s representation of Poland is generally favourable. Describing Cracow, he professed that: “it lies along the Vistula river, which also flows past the royal castle, placed on an elevated mound. Because of the splendour of its buildings, the affluence of all manner of goods, and various kinds of scholarly disciplines, the city itself contends with the illustrious towns of Germany.” In addition, Joris enthusiastically related his visit to the nearby Wieliczka salt mines, which attracted the attention of various foreign scholars and travellers. He also visited the poet Szymon Szymonowicz (1558-1629) in Lviv, and he befriended a Polish diplomat in Constantinople, who shared his interest for classical literature. Returning home, furthermore, Joris stayed in Zamość, a city founded in 1580 by the Grand Chancellor Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605), who was a friend of Joris’s father. Zamość also included an academy for higher education. Joris elaborately praised the city as “an effigy not just to Poland, but to the whole of Europe”, and he applauded the learnedness of Zamoyski himself. His flattering words were no doubt meant to strengthen his bonds with his Polish contacts. The account is an interesting testimony to the historical ties and friendships between Dutch and Polish scholars.

Joris’s representation of Poland is generally favourable. Describing Cracow, he professed that: “it lies along the Vistula river, which also flows past the royal castle, placed on an elevated mound. Because of the splendour of its buildings, the affluence of all manner of goods, and various kinds of scholarly disciplines, the city itself contends with the illustrious towns of Germany.” In addition, Joris enthusiastically related his visit to the nearby Wieliczka salt mines, which attracted the attention of various foreign scholars and travellers. He also visited the poet Szymon Szymonowicz (1558-1629) in Lviv, and he befriended a Polish diplomat in Constantinople, who shared his interest for classical literature. Returning home, furthermore, Joris stayed in Zamość, a city founded in 1580 by the Grand Chancellor Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605), who was a friend of Joris’s father. Zamość also included an academy for higher education. Joris elaborately praised the city as “an effigy not just to Poland, but to the whole of Europe”, and he applauded the learnedness of Zamoyski himself. His flattering words were no doubt meant to strengthen his bonds with his Polish contacts. The account is an interesting testimony to the historical ties and friendships between Dutch and Polish scholars.

Joris died in 1599, while sailing to India. The following year, his brother Dirk (1580-1663) visited Zamość as a student, and later even accompanied Jan Zamoyski on a war campaign in Livonia (roughly modern-day Latvia and Estonia).

The image comes from the account’s Dutch translation, published in Dordrecht in 1652.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 21.

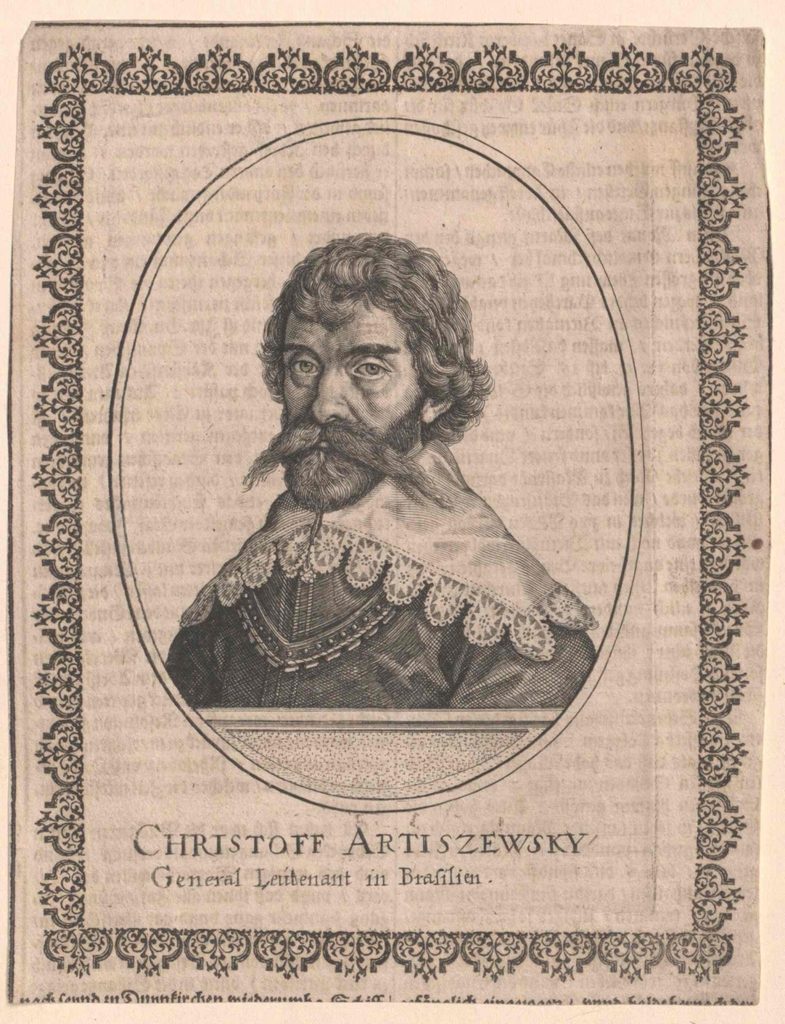

Numerous Poles live and work in the Netherlands today, and they have been doing so for hundreds of years. One of the most colourful and famous examples is the Protestant nobleman Krzysztof Arciszewski (1592-1656), an officer, engineer and author, who through became something of a celebrity in both the seventeenth-century Netherlands and Poland. Arciszewski first arrived in Holland in 1624, at the time of the Eight Years’ War, and until 1629 actively participated in a number of battles in both the Low Countries and France, always fighting on the Protestant side. For example, he partook in the Dutch attempts to end the Spanish siege of Breda in 1624-1625, and he fought in the siege of ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1629. Moreover, he studied military engineering and artillery at Leiden University. In 1629, Arciszewski was offered a three-year contract with the Dutch West-India Company and in the rank of captain left for Brazil. He celebrated multiple victories against the Portuguese, and was eventually promoted colonel. After the arrival, in 1637, of the new governor-general, Count John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), Arciszewski continued to play a key role in the Brazilian campaign, but disagreements between the two men led to Arciszewski’s return to Holland in 1639. He broke with the Dutch military, but stayed in the United Provinces until 1646, at which time he was summoned back to Poland and nominated royal general of artillery. Arciszewski next participated in a number of battles against the Turks and Cossacks, before retiring in 1649. He died in 1656.

Numerous Poles live and work in the Netherlands today, and they have been doing so for hundreds of years. One of the most colourful and famous examples is the Protestant nobleman Krzysztof Arciszewski (1592-1656), an officer, engineer and author, who through became something of a celebrity in both the seventeenth-century Netherlands and Poland. Arciszewski first arrived in Holland in 1624, at the time of the Eight Years’ War, and until 1629 actively participated in a number of battles in both the Low Countries and France, always fighting on the Protestant side. For example, he partook in the Dutch attempts to end the Spanish siege of Breda in 1624-1625, and he fought in the siege of ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1629. Moreover, he studied military engineering and artillery at Leiden University. In 1629, Arciszewski was offered a three-year contract with the Dutch West-India Company and in the rank of captain left for Brazil. He celebrated multiple victories against the Portuguese, and was eventually promoted colonel. After the arrival, in 1637, of the new governor-general, Count John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), Arciszewski continued to play a key role in the Brazilian campaign, but disagreements between the two men led to Arciszewski’s return to Holland in 1639. He broke with the Dutch military, but stayed in the United Provinces until 1646, at which time he was summoned back to Poland and nominated royal general of artillery. Arciszewski next participated in a number of battles against the Turks and Cossacks, before retiring in 1649. He died in 1656.

Did you hear about the medieval pilgrim from Gdańsk who visited the Netherlands? The story begins around Christmas 1444, when something remarkable occurred in Amersfoort, near Utrecht: a local girl, Margriet Gijsen, purportedly had three visions, in which God told her to go to a canal outside the city and find a statue of the Virgin Mary. Margriet did so and pulled the statue out of the icy water. This event was interpreted as a miracle, and Amersfoort quickly grew into an well-known place of worship. Pilgrims from all over Europe came to honour the statue, particularly on the Sunday before Pentecost. The miracle of Margriet and ca. 550 other miracles related to the statue are recorded in the so-called Mirakelboek, which starts in 1444 and ends in 1545. The statue was especially popular with shipmen and evoked in case of sea storms, shipwreck and drowning.

Did you hear about the medieval pilgrim from Gdańsk who visited the Netherlands? The story begins around Christmas 1444, when something remarkable occurred in Amersfoort, near Utrecht: a local girl, Margriet Gijsen, purportedly had three visions, in which God told her to go to a canal outside the city and find a statue of the Virgin Mary. Margriet did so and pulled the statue out of the icy water. This event was interpreted as a miracle, and Amersfoort quickly grew into an well-known place of worship. Pilgrims from all over Europe came to honour the statue, particularly on the Sunday before Pentecost. The miracle of Margriet and ca. 550 other miracles related to the statue are recorded in the so-called Mirakelboek, which starts in 1444 and ends in 1545. The statue was especially popular with shipmen and evoked in case of sea storms, shipwreck and drowning. The story can be related to a pilgrim’s badge from Amersfoort, which was found in or near Gdańsk. The badge depicts the moment when Margriet pulled the statue of Mary out of the water. Such badges were made at the place of worship and could be purchased by pilgrims, who then took them back home. The badge shows the importance and popularity of Amersfoort as a medieval pilgrimage site, which really was visited by people from Gdańsk. Perhaps the man from the story took a badge home as well…

The story can be related to a pilgrim’s badge from Amersfoort, which was found in or near Gdańsk. The badge depicts the moment when Margriet pulled the statue of Mary out of the water. Such badges were made at the place of worship and could be purchased by pilgrims, who then took them back home. The badge shows the importance and popularity of Amersfoort as a medieval pilgrimage site, which really was visited by people from Gdańsk. Perhaps the man from the story took a badge home as well…

Coming Tuesday is King’s Day in the Netherlands. Did you know that William of Orange, who is often called the Dutch “father of the fatherland”, had an interest in the royal elections in Poland in 1575? He may even have considered making a bid for the Polish throne himself. At the time, William was leading the Dutch in a war against Spain. In March 1575, his councillor Philips of Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde, visited Cracow, where he met with the Polish nobleman and influential Calvinist Piotr Zborowski. The Polish throne was at that time vacant, and preparations were being made for the election of a new monarch. Zborowski wrote to William, praising his struggle “for religion and for the freedom of your fatherland”, and explaining how Marnix’s visit had been essential for “our actions”. It is not known what these “actions” were, however. Perhaps Marnix was meant to inquire about William’s chances, should he submit his candidacy for the Polish throne. As King of Poland, William’s odds in the fight against Spain would increase significantly. On the other hand, William may not have considered entering the elections at all. Perhaps Marnix simply wished to offer support to the Polish Calvinists’ “actions”, trying to influence the royal elections in the hope of gaining the favour of the future king. In any case, William did not make an official bid for Polish power. Instead, Stephen Báthory was elected King of Poland in 1576.

Coming Tuesday is King’s Day in the Netherlands. Did you know that William of Orange, who is often called the Dutch “father of the fatherland”, had an interest in the royal elections in Poland in 1575? He may even have considered making a bid for the Polish throne himself. At the time, William was leading the Dutch in a war against Spain. In March 1575, his councillor Philips of Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde, visited Cracow, where he met with the Polish nobleman and influential Calvinist Piotr Zborowski. The Polish throne was at that time vacant, and preparations were being made for the election of a new monarch. Zborowski wrote to William, praising his struggle “for religion and for the freedom of your fatherland”, and explaining how Marnix’s visit had been essential for “our actions”. It is not known what these “actions” were, however. Perhaps Marnix was meant to inquire about William’s chances, should he submit his candidacy for the Polish throne. As King of Poland, William’s odds in the fight against Spain would increase significantly. On the other hand, William may not have considered entering the elections at all. Perhaps Marnix simply wished to offer support to the Polish Calvinists’ “actions”, trying to influence the royal elections in the hope of gaining the favour of the future king. In any case, William did not make an official bid for Polish power. Instead, Stephen Báthory was elected King of Poland in 1576.