Do you like a good pun? I know I do, and people have been loving wordplay for centuries. Some time ago, I came across the following seventeenth-century example, which is not only amusing, but also relates to my research – albeit in a small way.

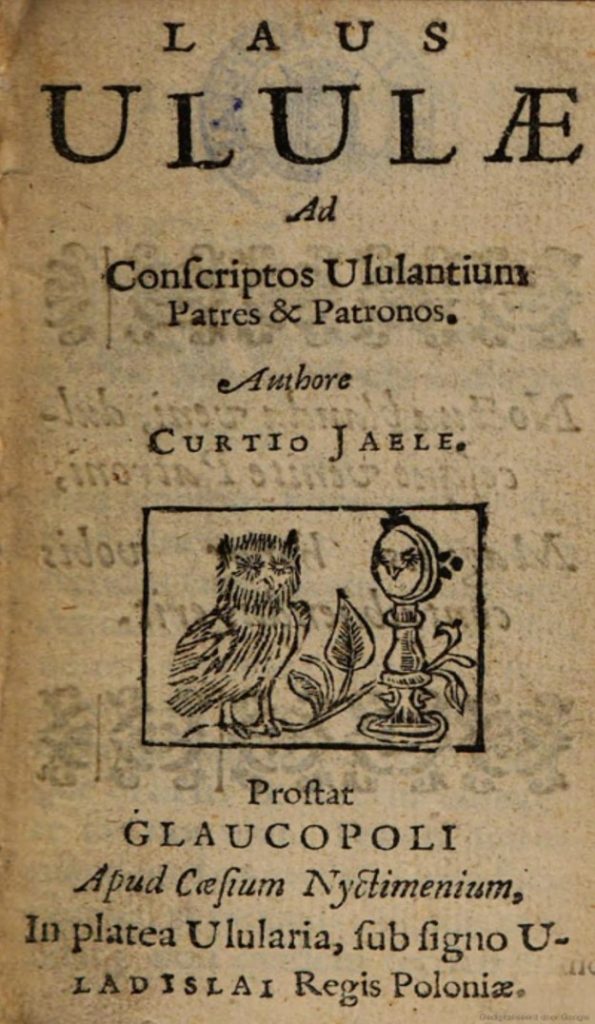

In 1640, the Dutch Protestant preacher Conradus Goddaeus published a Latin book entitled Laus Ululae, which translates as The Praise of the Owl. The work falls into the category of the so-called paradoxical encomium, or satirical eulogy, which became exceedingly popular following the success of Erasmus’s Moriae Encomium, The Praise of Folly. Illustrations adorning both the book’s frontispiece and the title page, moreover, show an owl looking into a mirror: a clear reference to the well-known tales of Till Eulenspiegel. In the Laus Ululae, Goddaeus (who used the pseudonym Curtius Jael) jokingly praises the owl and elaborately discusses the bird’s many traits and (sometimes strikingly human) virtues. P.C. Hooft gave the book a positive “review”, and its numerous reprints suggest that it was quite popular during the seventeenth century. It was also translated into Dutch (1664) and English (1727).

What makes this book interesting for me is its title page, which is filled with puns. In the first few editions, issued during the 1640s, the imprint information reads as follows: Prostat GLAUCOPOLI Apud Caesium Nyctimenium, In platea Ulularia, sub signo ULADISLAI Regis Poloniae. This can be translated as: For sale in Owl City at Caesius (the “blue-grey”) Nyctimenius (“moonlit-night”) on Owl Street, under the sign of Władysław, King of Poland.

The play on Greek and Latin words would have been obvious to most learned readers (Glaucopoli, for example, is simply a combination of the Greek words γλαῦξ, meaning “owl”, and πόλις, meaning “city”). But what is Władysław, the King of Poland, doing on that title page?

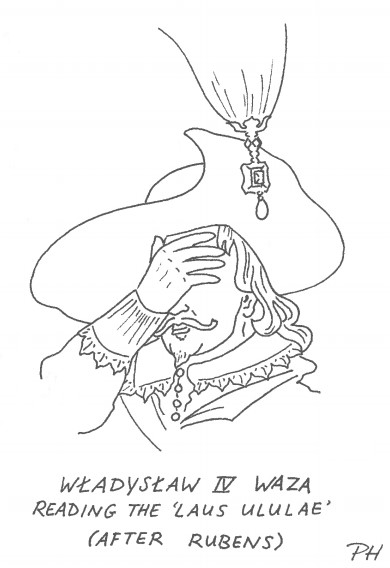

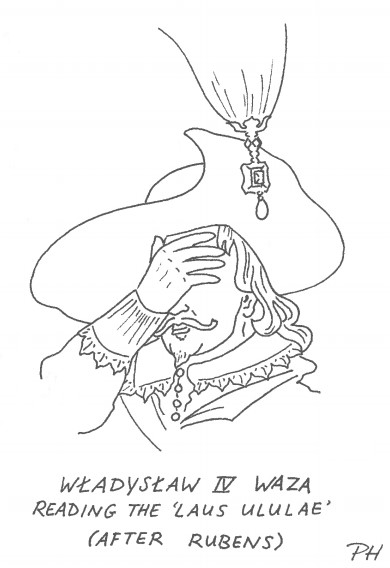

Let us first establish who this king was. Between 1632 and 1648, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was ruled by Władysław IV Waza. As the Laus Ululae was first published in 1640, Goddaeus was obviously referring to the Polish monarch in power at the time. Indeed, this is confirmed by the fact that the Latin editions printed after 1648, the year in which Władysław died, no longer feature him on their title page.

Still, this does not explain why Goddaeus chose to suggest that his work could be purchased at a bookseller who had a shop sign showing Władysław IV Waza. Of course, there was no such sign, just as there was no Owl City, no Owl Street and no bookseller named Caesius Nyctimenius. It has been suggested that Goddaeus, a Protestant preacher, referred to the Catholic Polish monarch in order to mock him, and this is not altogether impossible: after all, the entire book is a satirical eulogy. Tying it to Władysław so explicitly by bringing to mind his portrait, and implying that the bookseller had selected the Polish king’s face as his shop’s “logo”, can easily lead one to think of Władysław as “The Owl King”. This may sound cool, perhaps, but taking into account the fact that the Laus Ululae is nothing but satire, any association between the Polish king and owls can hardly be read as a compliment.

Yet the main reason why Goddaeus introduced Władysław on the title page is arguably much simpler. As mentioned, the imprint information is full of puns, and Władysław’s name is used as such as well. The Latin spelling of Władysław is Ladislaus or Vladislaus, which can also be spelled as Uladislaus. Compare this to the title of Goddaeus’s book, and the similarities between the two will immediately become apparent. On one of the edition’s title pages, in fact, the “U” is even intentionally separated from the rest of the king’s name, making it impossible to miss Goddaeus’s joke.

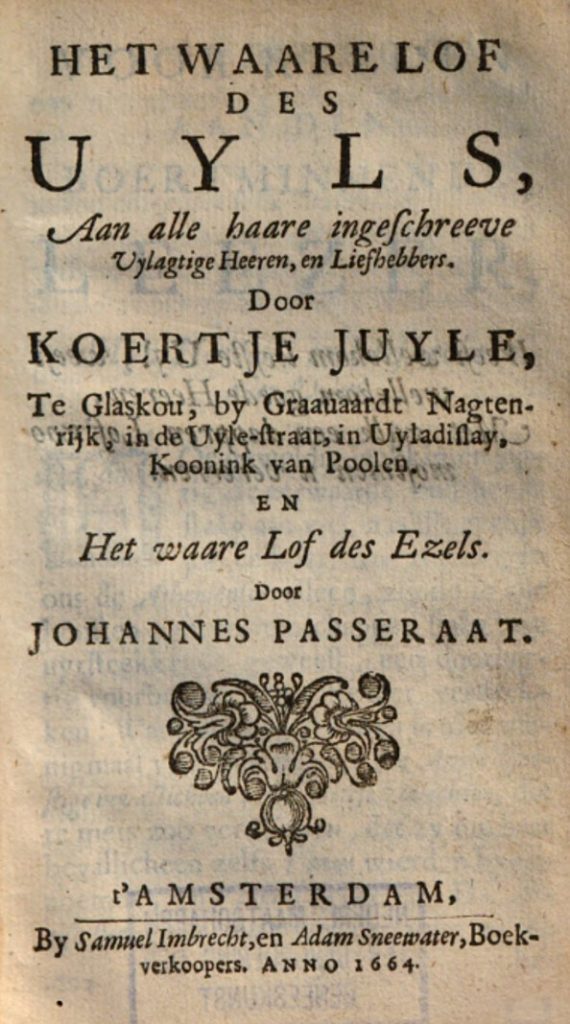

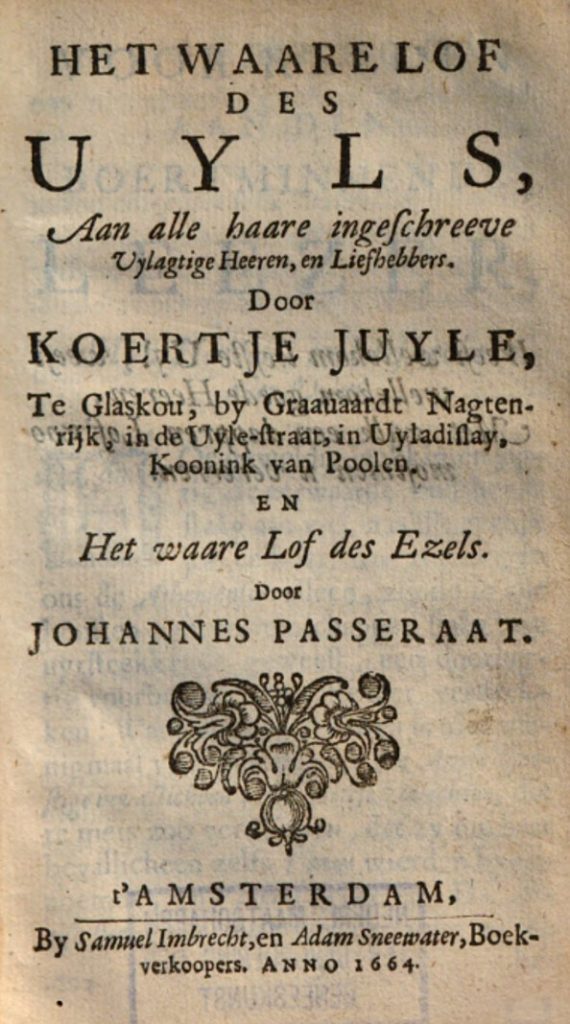

The pun was not lost on the Dutch audience. In 1664, a Dutch translation of the text was published, including a translated version of the original title page (even though, as mentioned, Władysław had died in 1648). Naturally, the play on words had to be rendered in Dutch as well: the book is now said to have been published in “Glaskou” (“Glasgow”, a playful reference to γλαῦξ), at a bookseller named “Graauaardt Nagtenrijk” (something along the lines of “Greyman Nightrealm”) on “Uyle-straat” (“Owl Street”). Moreover, the king’s name has been adapted to incorporate “uyl”, the Dutch word for “owl”, and ends with a “y” in order to mirror the Latin original’s genitive (“Uladislai”). The imprint information thus concludes with “in Uyladislay, Kooninck van Poolen”, which can be translated as “in [the shop beneath the sign of] Owladislaus, King of Poland”.

The pun was not lost on the Dutch audience. In 1664, a Dutch translation of the text was published, including a translated version of the original title page (even though, as mentioned, Władysław had died in 1648). Naturally, the play on words had to be rendered in Dutch as well: the book is now said to have been published in “Glaskou” (“Glasgow”, a playful reference to γλαῦξ), at a bookseller named “Graauaardt Nagtenrijk” (something along the lines of “Greyman Nightrealm”) on “Uyle-straat” (“Owl Street”). Moreover, the king’s name has been adapted to incorporate “uyl”, the Dutch word for “owl”, and ends with a “y” in order to mirror the Latin original’s genitive (“Uladislai”). The imprint information thus concludes with “in Uyladislay, Kooninck van Poolen”, which can be translated as “in [the shop beneath the sign of] Owladislaus, King of Poland”.

The case shows us how a Polish monarch made his way into Dutch seventeenth-century “popular” culture: starting in 1640, a pun featuring Władysław IV Waza was putting smiles on Dutch faces. Indeed, it even managed to put one on mine in 2018.

The pun was not lost on the Dutch audience. In 1664, a Dutch translation of the text was published, including a translated version of the original title page (even though, as mentioned, Władysław had died in 1648). Naturally, the play on words had to be rendered in Dutch as well: the book is now said to have been published in “Glaskou” (“Glasgow”, a playful reference to γλαῦξ), at a bookseller named “Graauaardt Nagtenrijk” (something along the lines of “Greyman Nightrealm”) on “Uyle-straat” (“Owl Street”). Moreover, the king’s name has been adapted to incorporate “uyl”, the Dutch word for “owl”, and ends with a “y” in order to mirror the Latin original’s genitive (“Uladislai”). The imprint information thus concludes with “in Uyladislay, Kooninck van Poolen”, which can be translated as “in [the shop beneath the sign of] Owladislaus, King of Poland”.

The pun was not lost on the Dutch audience. In 1664, a Dutch translation of the text was published, including a translated version of the original title page (even though, as mentioned, Władysław had died in 1648). Naturally, the play on words had to be rendered in Dutch as well: the book is now said to have been published in “Glaskou” (“Glasgow”, a playful reference to γλαῦξ), at a bookseller named “Graauaardt Nagtenrijk” (something along the lines of “Greyman Nightrealm”) on “Uyle-straat” (“Owl Street”). Moreover, the king’s name has been adapted to incorporate “uyl”, the Dutch word for “owl”, and ends with a “y” in order to mirror the Latin original’s genitive (“Uladislai”). The imprint information thus concludes with “in Uyladislay, Kooninck van Poolen”, which can be translated as “in [the shop beneath the sign of] Owladislaus, King of Poland”.

onderdompeling in de zee, ofwel één, ofwel drie keer: nadat men namelijk een touw onder de onderkant van een schip door zou hebben gehaald, zouden sommigen van hen, vastgebonden aan hun nek, onder het schip worden getrokken, alsof ze onder een juk door gingen; ze zouden geluk hebben als ze daarbij toevallig niet zouden stikken of gewurgd worden. Hoewel ze de doodstraf hebben gekregen, wordt hun toch deze gratie verleend: aan hun hand wordt een spons vastgemaakt, waar ze hun ondergedompelde neus en mond in kunnen stoppen en zo kunnen ademen.”

onderdompeling in de zee, ofwel één, ofwel drie keer: nadat men namelijk een touw onder de onderkant van een schip door zou hebben gehaald, zouden sommigen van hen, vastgebonden aan hun nek, onder het schip worden getrokken, alsof ze onder een juk door gingen; ze zouden geluk hebben als ze daarbij toevallig niet zouden stikken of gewurgd worden. Hoewel ze de doodstraf hebben gekregen, wordt hun toch deze gratie verleend: aan hun hand wordt een spons vastgemaakt, waar ze hun ondergedompelde neus en mond in kunnen stoppen en zo kunnen ademen.”