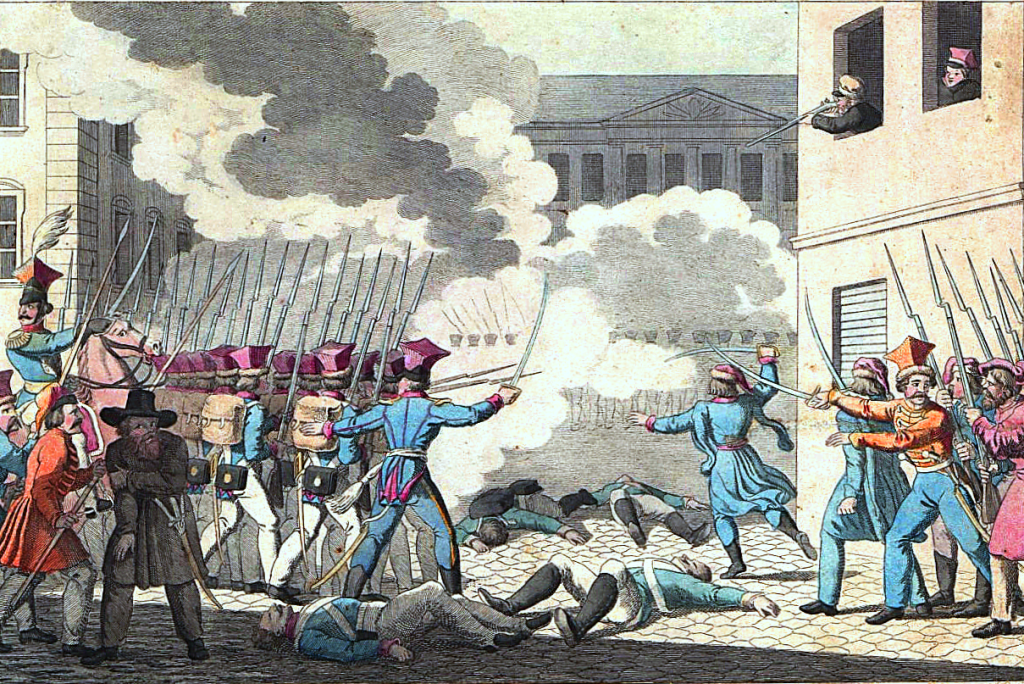

Dutch interest in Ukraine is not something new. As early as the seventeenth century, Dutch media reported on political developments in lands that were already known as Ukrainian territories. At that time, the lands which currently lie within Ukraine’s borders were a bone of contention for Poles, Russians, Cossacks, and Tatars. Dutch poets also wrote about these struggles, especially if they were important to the Dutch economy.

In 1649, for example, the renowned poet Joost van den Vondel commented on Tatar raids in Ukrainian territories, which “laid Poland in ashes” and “threatened us here with famine”: a clear reference to the grain trade between Poland and the Dutch Republic. Vondel obviously knew that large amounts of grain were produced in Ukraine, which at the time formed part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. From the south, the grain was then transported to Gdańsk, where it was bought in bulks by Dutch merchants.

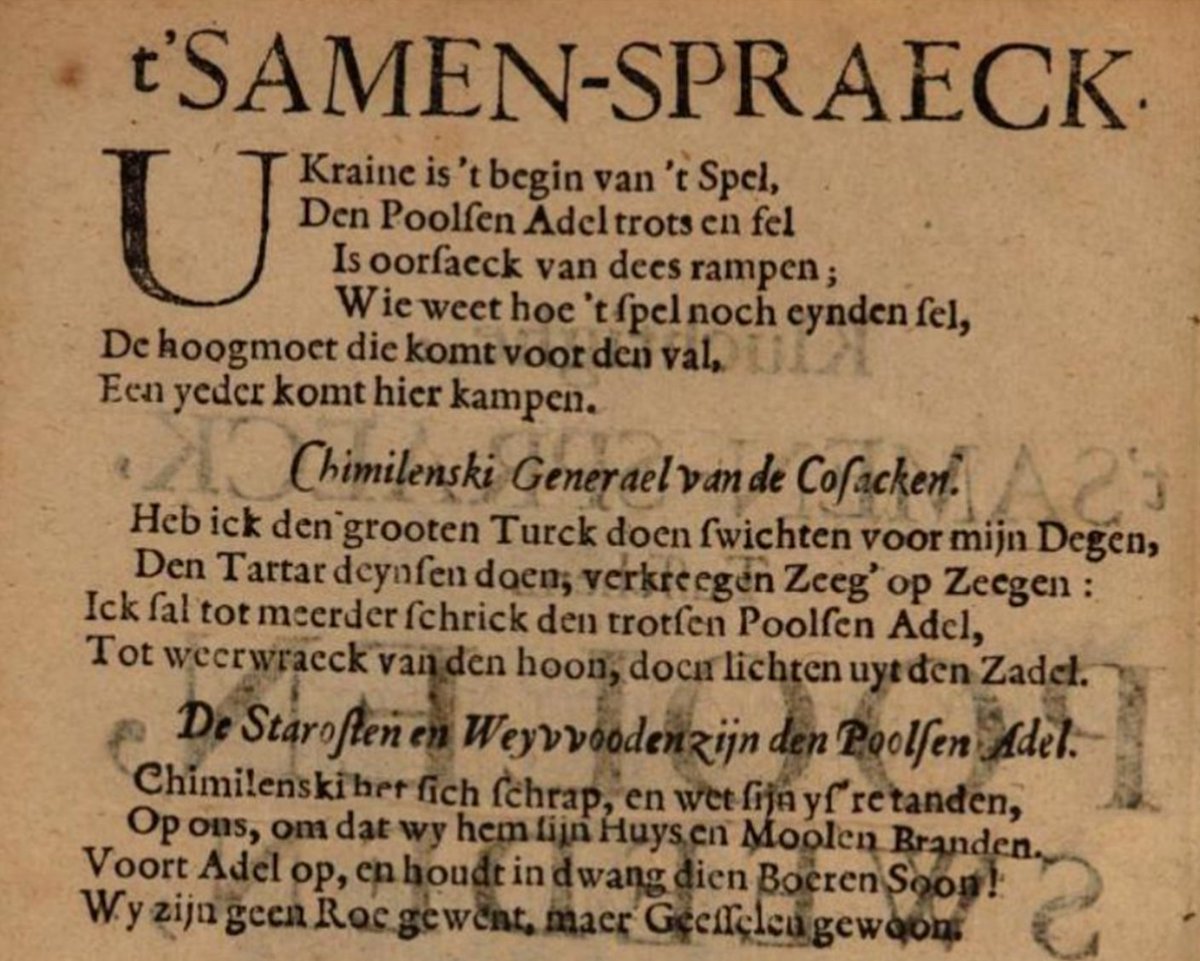

A few years later, in 1657, the anonymous author of a Dutch pamphlet reacted to the many wars which crippled the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: it was fighting the Cossacks, Tatars, Russians, and Swedes all at once – and was facing heavy losses. According to the author, the proud Polish nobles themselves were to blame:

Ukraine is the beginning of the game,

The Polish nobility, proud and fierce

Is the cause of these disasters;

Who knows how the game will end,

Pride comes before a fall,

Everyone comes to fight here.

These verses obviously refer to the 1648 Cossack Uprising, led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, who according to the poem aimed to lift “the proud Polish nobility from its saddle”. Later on, the focus shifts to the Swedish invasion of Poland, and the Dutch author argues in favor of sending aid to Gdańsk in order to protect the grain trade.

One final example dates from 1671. The poet Joannes Antonides van der Goes once again linked the ongoing fighting in Ukrainian territories with threats to the Dutch grain trade. Poland could feed the whole world, he wrote, if the country were not involved in wars with the Tatars, Turks, and Cossacks, led this time by hetman Petro Doroszenko. Echoing the earlier poem, Van der Goes stated that the Cossacks threatened to “lift the Polish nobility from its saddle”.

These examples make clear that Dutch readers and writers had a keen interest in political developments in Ukraine, which was essential to the Dutch economy due to the grain it produced. To this day, Ukraine is one of the largest grain exporters in the world.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 30.

In July 1606, a young student called Samuel Korecki inscribed his name into the album amicorum (“book of friends”) of the Dutch scholar and mayor of Harderwijk, Ernst Brinck. Korecki’s name features amongst numerous well-known men of the time, such as Galileo Galilei. But who was he?

In July 1606, a young student called Samuel Korecki inscribed his name into the album amicorum (“book of friends”) of the Dutch scholar and mayor of Harderwijk, Ernst Brinck. Korecki’s name features amongst numerous well-known men of the time, such as Galileo Galilei. But who was he?

This time of year, many of us have a nativity scene in our homes. They commonly include the Three Kings, also known as Wise Men or Magi, who came to honour Christ after his birth. These Kings are often dressed in long oriental robes and turbans. What is less commonly known, is that such a look in the previous centuries was sometimes associated with Polish dress. This can be exemplified by a gable stone showing a ‘Pool’, which is dated 1688, and which adorns a building on the Kerkstraat 322 in Amsterdam.

This time of year, many of us have a nativity scene in our homes. They commonly include the Three Kings, also known as Wise Men or Magi, who came to honour Christ after his birth. These Kings are often dressed in long oriental robes and turbans. What is less commonly known, is that such a look in the previous centuries was sometimes associated with Polish dress. This can be exemplified by a gable stone showing a ‘Pool’, which is dated 1688, and which adorns a building on the Kerkstraat 322 in Amsterdam. This is why the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam looks the way he does. His clothing – which even includes a turban – and his posture are reminiscent of a man in a print by the Dutch engraver Lucas Vorsterman, after the Adoration of the Magi by the famed painter Peter Paul Rubens, a painting from 1621. Rubens in turn based himself on Italian illustrations. It is likely that the gable stone’s maker referred to the same pictorial tradition. This is how the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam is related to nativity scenes.

This is why the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam looks the way he does. His clothing – which even includes a turban – and his posture are reminiscent of a man in a print by the Dutch engraver Lucas Vorsterman, after the Adoration of the Magi by the famed painter Peter Paul Rubens, a painting from 1621. Rubens in turn based himself on Italian illustrations. It is likely that the gable stone’s maker referred to the same pictorial tradition. This is how the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam is related to nativity scenes. Last week, it was announced that the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam – with financial aid from the Dutch state and several institutions – intends to buy ‘The Standard Bearer’, a painting by Rembrandt from 1636. Such standard bearers were high-placed members of town militias, not necessarily soldiers. Still, the painting offers an opportunity to reflect on a little-known aspect of Dutch-Polish historical relations: Polish soldiers in the seventeenth-century Dutch army. A travel account by the Pole Sebastian Gawarecki, written during the 1640s, discusses his stay in the Northern Netherlands alongside Marek and Jan Sobieski – the later king of Poland. On 16 May 1646, in the town of Bergen op Zoom, Gawarecki and the Sobieski brothers met “a Pole from Warsaw, who for some years now serves in the Dutch army as a standard bearer, and whom our Polish king [Władysław IV Waza] keeps in Holland at his own expense.” It is unknown who this Polish standard bearer was, but it was not unheard of for Poles to fight in the Dutch army, even if they were Catholics.

Last week, it was announced that the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam – with financial aid from the Dutch state and several institutions – intends to buy ‘The Standard Bearer’, a painting by Rembrandt from 1636. Such standard bearers were high-placed members of town militias, not necessarily soldiers. Still, the painting offers an opportunity to reflect on a little-known aspect of Dutch-Polish historical relations: Polish soldiers in the seventeenth-century Dutch army. A travel account by the Pole Sebastian Gawarecki, written during the 1640s, discusses his stay in the Northern Netherlands alongside Marek and Jan Sobieski – the later king of Poland. On 16 May 1646, in the town of Bergen op Zoom, Gawarecki and the Sobieski brothers met “a Pole from Warsaw, who for some years now serves in the Dutch army as a standard bearer, and whom our Polish king [Władysław IV Waza] keeps in Holland at his own expense.” It is unknown who this Polish standard bearer was, but it was not unheard of for Poles to fight in the Dutch army, even if they were Catholics.