One of my favourite pastimes is to engage with younger generations about language and history. I could do so again yesterday, this time to talk about new research that I have only just completed, on Dutch-Polish bilingualism in the 17th century: who could speak Polish and Dutch at the time, where and why? My presentation included Dutch traders in Gdańsk, Polish students in Franeker and Leiden, and Jewish translators in Amsterdam. What made this event special was the fact that my audience itself was bilingual, as I was a guest at Fundacja Polskie Centrum Edukacji i Kultury Lokomotywa in Amsterdam, where I gave a talk about Dutch-Polish historical relations last year as well. Lokomotywa is a Saturday school for children of Polish descent (there are dozens of such schools in the Netherlands – I myself attended the Polish school in Goirle for many years). Talking to bilingual children about bilingualism: I was over the moon, and I think they liked it too, especially when we got to the quiz about old Polish and Dutch words!

1642: The First Polish Texts in the Netherlands (NL Embassy in PL)

On 17 March, the yearly Wierszowisko festival took place in Wijchen, the Netherlands: almost 140 children from Polish schools across the Netherlands performed on stage, giving fabulous renditions of Polish poems. In this manner, the festival helps to keep the Polish language – and Polish poetry in particular – alive in the Netherlands. I was happy to be one of the judges, just as last year. I was greatly impressed by the enthusiasm, the theatrical talents and the language proficiency shown by all the young contestants.

The roots of this literary Polish presence go back hundreds of years: Polish texts were published in the Netherlands as early as the seventeenth century! Interestingly, moreover, most of them were poems, written by Polish students and printed in Franeker, in Frisia. As far as we know, the first two were published in 1642, and several more followed in the rest of the seventeenth century. These poems were written for specific occasions, for example to celebrate someone’s promotion, applaud a new book, or express grief over someone’s passing. The addressees of these poems apparently knew (some) Polish. Franeker at that time had a university, which was frequently visited by (Calvinist) Polish students. The university’s popularity was boosted by two Polish professors: Jan Makowski (Joannes Maccovius) and Mikołaj Arnold (Nicolaus Arnoldus). Arnold himself was the author of two published Polish poems, but he also became proficient in Dutch.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 51.

A Dutch School in Medieval Poland (NL Embassy in PL)

Migration between Poland and the Netherlands is currently flourishing, but it is not purely a modern phenomenon. In fact, examples reach back as far as the Middle Ages! An interesting, though relatively obscure case of Dutchmen settling in Poland dates from the late fifteenth century. The Municipal Council of Chełmno, a Hanseatic town in the north of Poland, at that time wished to establish a school for higher education. To that end, they invited a group of teachers from the Brethren of the Common Life, who came from Zwolle and arrived in Chełmno in 1473. The Brethren of the Common Life formed a Roman Catholic religious community, that was founded in the fourteenth century by the preacher and educator Geert Grote. The Brethren adhered to the so-called Modern Devotion, a simple and pious lifestyle in service of Christ.

The school in Chełmno became a successful and respected centre of education, which included a large library. Polish scholars have argued that the Brothers also devoted themselves to book production: it is likely that they brought along all necessary equipment from Zwolle, including a printing press. If this was indeed the case, the settlers were among the earliest book printers in Poland! Meanwhile, the Municipal Council of Chełmno looked after the needs of the Brothers, granting them several buildings in the city and even some villages, which generated income. Unfortunately, due to financial and other problems, the Brothers eventually returned to the Low Countries and the school closed its doors in 1539. Because the Brothers left such a sizeable imprint on Chełmno and its surroundings, however, their activities form an important episode in the history of Dutch-Polish relations. Indeed, some scholars contend that the school was attended by one very famous pupil: Mikołaj Kopernik (Nicolaus Copernicus).

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 50.

2003/4: Polish Art in Leiden (NL Embassy in PL)

Twenty years ago, as Poland prepared to join the EU in 2004, a selection of Polish graphic art was on view at the Stadsbouwhuis in Leiden. The exhibition was organized by Stichting Witryna, which aims to give a stage to Polish art in the Netherlands, particularly modern graphic art. In late 2003, visitors could admire a range of prints by several artists from Toruń, which is a sister city of Leiden. Four artists employed at the Nicolaus Copernicus University of Toruń – Józef Słobosz, Jan Baczyński, Piotr Gojowy and Marek Basiula – brought along mezzotints, woodcuts and other prints. In addition, Dutch-Polish sculptor Aleksandra Zielińska, who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Wrocław, contributed with multiple artistic 3D-installations.

With the exhibition, Stichting Witryna strengthened the cultural ties between Leiden and Toruń, but also between the Netherlands and Poland, when the EU stood to welcome Poland as one of its newest members.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 49.

1686: Dutch Crowds Gather to Praise Jan III Sobieski (NL Embassy in PL)

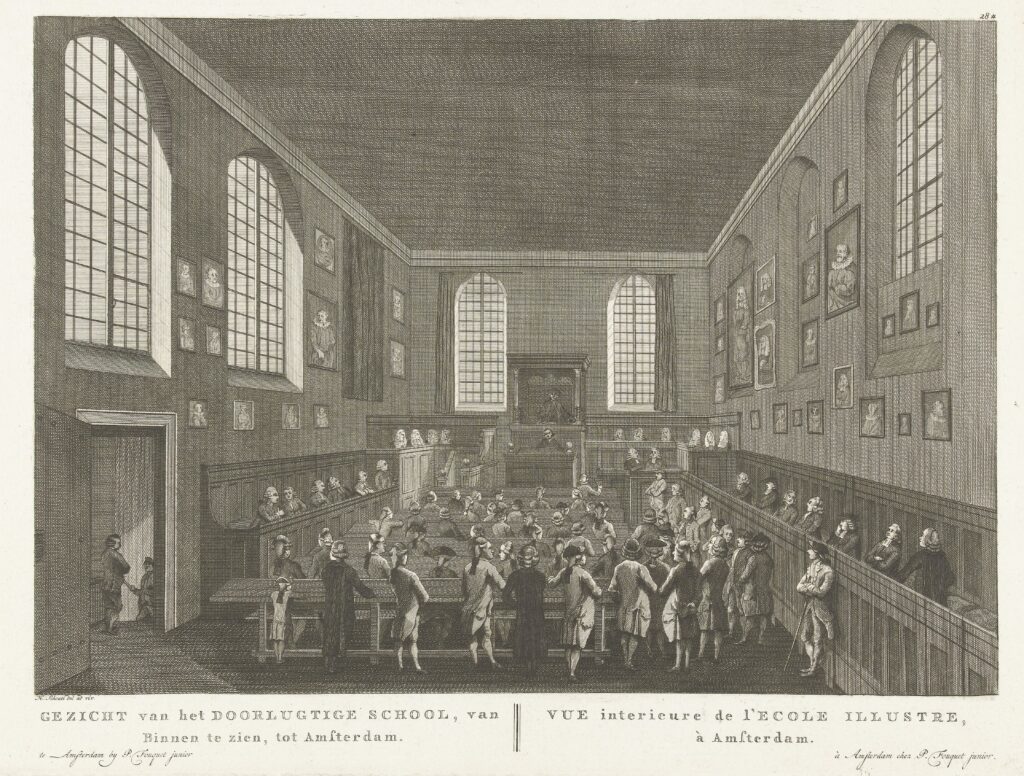

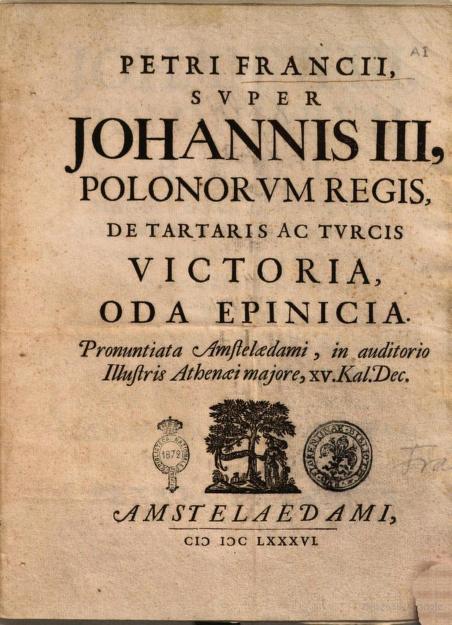

On this day in 1686, people in Amsterdam gathered to praise King Jan III Sobieski of Poland. In the city’s Athenaeum Illustre, the forerunner of the University of Amsterdam, the Dutch professor of ancient rhetoric Petrus Francius delivered a public reading of a poem he had written in Sobieski’s honour. The cause for this event was the Siege of Buda, which took place in the summer of 1686. The armies of the so-called Holy League at that time reclaimed the city of Buda, ending almost 150 years of Ottoman rule. Francius subsequently wrote four elaborate poems about the Holy League’s wars against the Ottomans, which he published and recited in the Athenaeum Illustre and the New Church of Amsterdam. Sobieski played no part in the Siege of Buda, but he had made a name for himself as a grand Christian champion, especially after his actions at the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

The poem by Francius is an overwhelming appraisal covering nineteen pages, which pulls out all the stops. The Polish king’s bravura and success on the battlefield is sensationally described and contrasted with the supposed shame and infamy of his enemies. Moreover, Francius compared Sobieski with mythological figures like Mars and Hercules, but also with historical rulers such as Charlemagne and Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. In addition, the Dutchman extolled Sobieski’s sons, Jakub and Aleksander. This part of the eulogy aligns with Sobieski’s contemporary propaganda, which after 1683 pushed his (failed) agenda of establishing a royal dynasty. The published version of the poem shows that Francius used various sources, including the words of a Polish diplomat who resided in Holland.

The poem by Francius is an overwhelming appraisal covering nineteen pages, which pulls out all the stops. The Polish king’s bravura and success on the battlefield is sensationally described and contrasted with the supposed shame and infamy of his enemies. Moreover, Francius compared Sobieski with mythological figures like Mars and Hercules, but also with historical rulers such as Charlemagne and Gustav II Adolph of Sweden. In addition, the Dutchman extolled Sobieski’s sons, Jakub and Aleksander. This part of the eulogy aligns with Sobieski’s contemporary propaganda, which after 1683 pushed his (failed) agenda of establishing a royal dynasty. The published version of the poem shows that Francius used various sources, including the words of a Polish diplomat who resided in Holland.

Most of the people in the Athenaeum Illustre that day must have been educated: the poem was written in Latin. One of them was Joan Pluimer, the director of the Amsterdam Schouwburg, who responded to Francius’s performance with a Dutch poem of his own. According to Pluimer, the entire audience stood in amazement:

Who would not stammer, stray, faced with the virtue of a god [Sobieski],

Besides only Francius? He portrays the war hero [Sobieski];

The high school [Athenaeum Illustre] then seems a bulwark in the field;

His eyes shoot lightning, while he thunders with words.

Learned and unlearned, all stand amazed,

And see nature and art in the highest form.

Furthermore, letters by and to Francius reveal that he sent his poem to other people who appreciated his work, both in the Dutch Republic and abroad. The composition may even have reached Poland: in early 1687, the aforementioned Polish diplomat sent an unspecified panegyric of Sobieski from Holland to Gdańsk. The Polish king was an avid book collector. Perhaps he read Francius’s poem himself?

The case of Francius is the most telling literary example of the fame Sobieski enjoyed in the Northern Netherlands: ever since his royal election in 1674, numerous Dutch artists, artisans and authors had celebrated Sobieski through prints, poems, pamphlets, theatre plays and other means. I briefly wrote about some of these instances here and here, and I have dedicated this article to the Dutch reception of Sobieski prior to his victory at Vienna. My PhD thesis offers even more elaborate information, and also discusses Dutch reactions to Sobieski after 1683, including the poems by Petrus Francius and Joan Pluimer.

*I originally wrote (a different version of) this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 48.

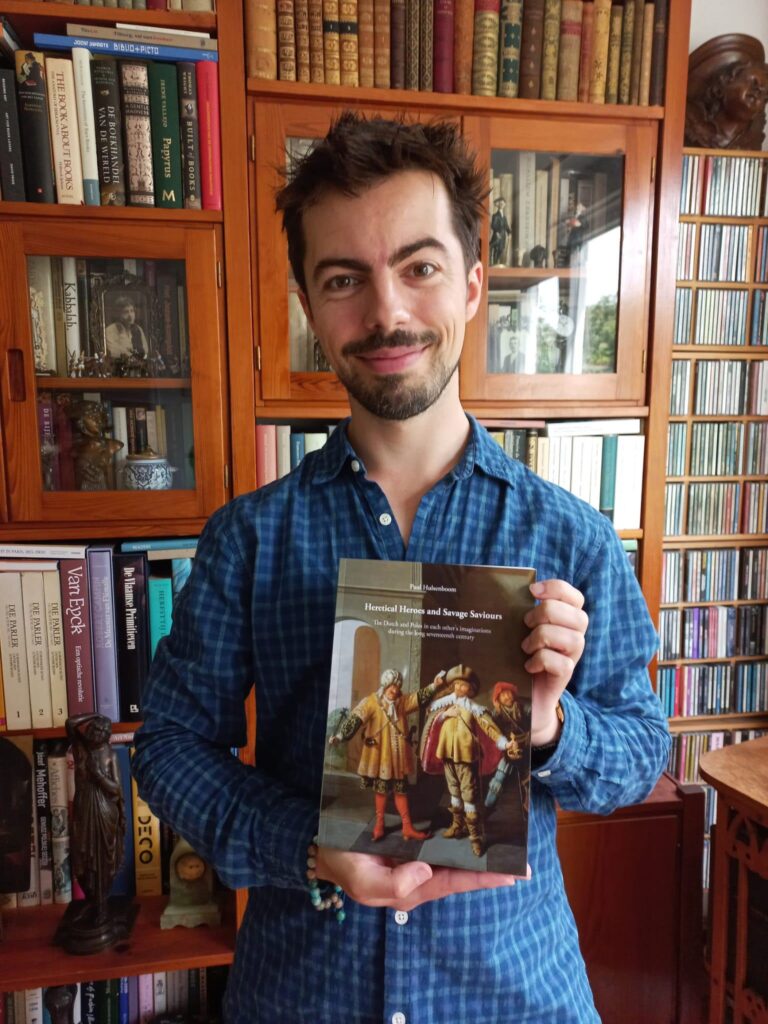

PhD Thesis Defended!

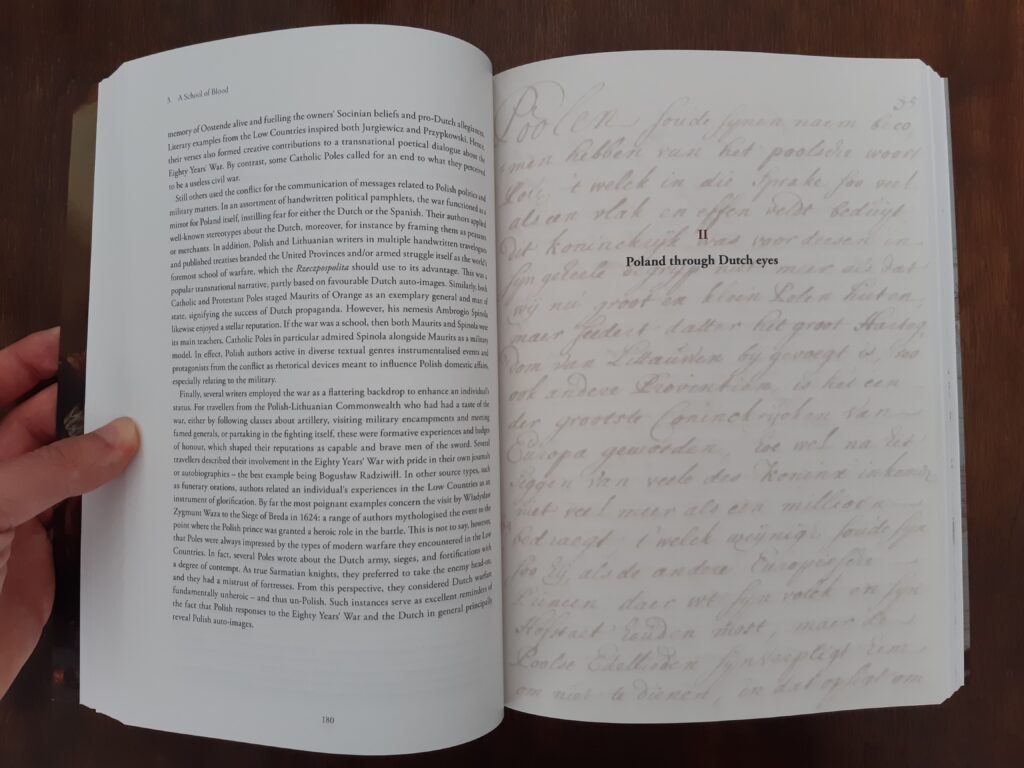

On 24 October, I successfully defended my PhD thesis entitled Heretical Heroes and Savage Saviours. The Dutch and Poles in each other’s imaginations during the long seventeenth century. I thoroughly enjoyed the ceremony and subsequent celebrations: a reception, dinner and party with family and friends! My thanks go out to all those who made the day’s festivities possible, especially my supervisors prof. dr. Lotte Jensen and prof. dr. Johan Oosterman, the members of the manuscript committee, and my paranymphs dr. Lieke Verheijen-van Wijk and dr. Alan Moss.

My PhD thesis can be downloaded for free here. Interested in a summary? This video shows a recording of the brief presentation I gave at the start of the defence ceremony (in Dutch).

Dutch and English Introductions to my PhD Thesis

Radboud University has published a text on my PhD thesis, which offers an introduction to my research and discusses some of my main conclusions. It forms the result of a conversation I had with Wies Bakker, who works at the university’s Marketing and Communications department. An English translation was published here by Radboud Recharge.

The Dutch version was subsequently republished here by the website Historiek.nl.

1654: A Polish Poet Mourns a Dutch Disaster (NL Embassy in PL)

On 12 October 1654, the Delft Thunderclap took place. At approximately 10:30 a.m., a quarter of the town was wiped away by an explosion in the gunpowder magazine of Holland, which was located in or near a former monastery. The cause of the explosion has never been established, but the story goes that a clerk entered the magazine carrying a burning lantern, sparks of which may have set fire to the highly flammable stash of gunpowder inside. The disaster elicited numerous responses by authors and artists from the Northern and Southern Netherlands, but it also inspired a reaction from Poland: in Gdańsk, the local historian, doctor, and teacher Joachim Pastorius showed solidarity with the Dutch victims by writing a mournful Latin poem, which he published in 1657. Pastorius had many Dutch contacts and likely based his verses on Dutch sources, specifically a famous poem by Joost van den Vondel. He probably sent it to his Dutch friends as a sign of compassion. Pastorius’s composition thus forms a fine example of the literary relations between Poland and the Dutch Republic. Moreover, the disastrous Delft Thunderclap provided him with the opportunity to shape an emotional community which bridged the two countries.

For a detailed analysis of Pastorius’s engagement with the disaster, see my Open Access chapter ‘Early Modern Community Formation Across Northern Europe. How and Why a Poet in Poland Engaged with the Delft Thunderclap of 1654’, in: H. van Asperen and L. Jensen (eds.), Dealing with Disasters from Early Modern to Modern Times. Cultural Responses to Catastrophes (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2023) 61-81.

*I originally wrote (a different version of) this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 47.

PhD Thesis Finished!

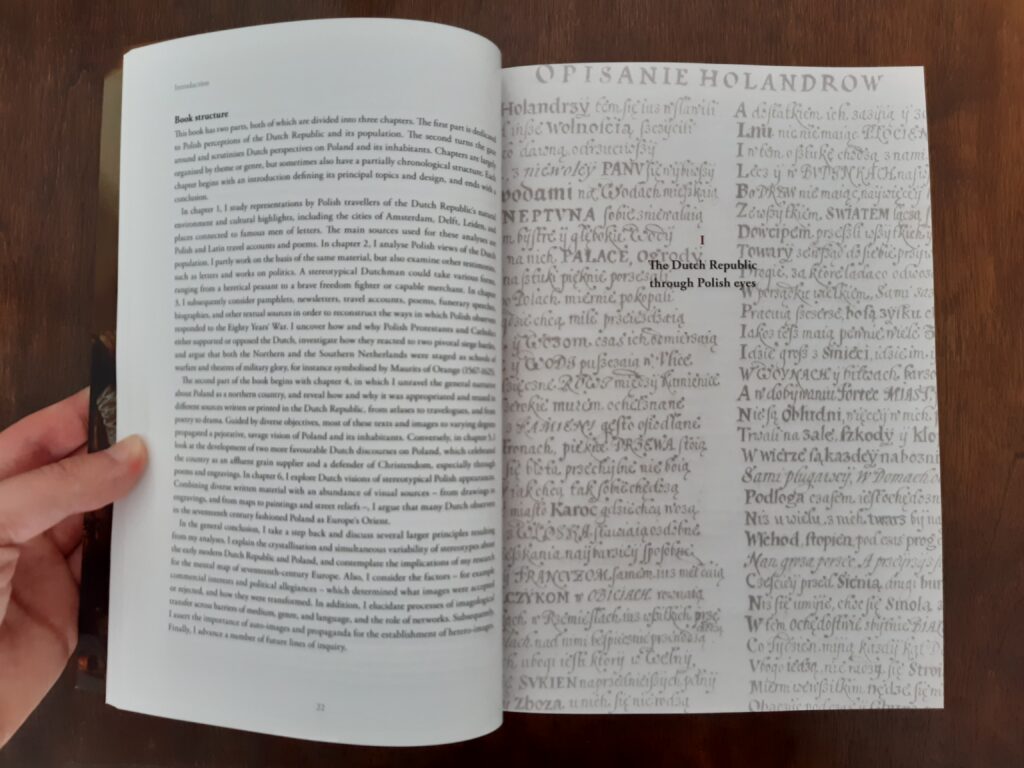

This is it: Heretical Heroes and Savage Saviours. The Dutch and Poles in each other’s imaginations during the long seventeenth century, the final version of my PhD thesis! Almost 600 pages and over 150 illustrations which together tell a story about how the Dutch and Poles imagined each other during the long seventeenth century, and how we can explain these representations. From the United Provinces as a natural and cultural marvel and school of warfare to the Dutch population as Calvinist, freedom-loving peasants, and from Poland as a grain-rich trading partner and champion of Christendom to the Poles themselves as northern savages and inhabitants of Europe’s Orient. The book will be available in Open Access after my defence on 24 October!

This is it: Heretical Heroes and Savage Saviours. The Dutch and Poles in each other’s imaginations during the long seventeenth century, the final version of my PhD thesis! Almost 600 pages and over 150 illustrations which together tell a story about how the Dutch and Poles imagined each other during the long seventeenth century, and how we can explain these representations. From the United Provinces as a natural and cultural marvel and school of warfare to the Dutch population as Calvinist, freedom-loving peasants, and from Poland as a grain-rich trading partner and champion of Christendom to the Poles themselves as northern savages and inhabitants of Europe’s Orient. The book will be available in Open Access after my defence on 24 October!

Scroll down for an impression of the book’s contents:

Dutch-Polish Relations During the “Deluge” (NL Embassy in PL)

Every Pole has learned about the ‘Potop’ or ‘Deluge’: the Swedish invasion of Poland, part of the Second Northern War, which started in 1655. What is less well known, however, is that the Dutch Republic played a part in that war as well. On 10 July 1656, the States-General and the representatives of Gdańsk and Poland signed a concept treaty in The Hague, which stipulated that the Dutch (together with the Danes) would come to the city’s aid in case it were attacked. The States furthermore considered offering Gdańsk financial and military assistance in the form of loans and soldiers. In turn, the Dutch demanded the same freedom of commerce as merchants from Gdańsk itself. The city’s authorities still needed to ratify the treaty, however.

In late July, a large Dutch fleet was sent to the Baltic in order to lend support to Gdańsk and put pressure on the Swedes. Meanwhile, a Dutch diplomatic delegation tried to include Gdańsk in an agreement with Sweden, which would force the town to adopt a neutral position in the conflict. As this would violate the city’s fealty to Poland, however, its officials did not approve. Moreover, they refused to ratify the concept treaty signed on 10 July. The Dutch ambassadors subsequently left Gdańsk in early October, together with the bulk of the fleet. As a final token of support, several hundred Dutch soldiers were temporarily stationed in Gdańsk. A local author thanked the Dutch with a Latin poem, expressing the hope for future cooperation.

In 1658, a Dutch fleet defeated the Swedes during the Battle of the Sound. The success prompted numerous celebratory reactions from Dutch writers and artists, who applauded the Dutch victory and deplored the sorry state of Poland, which had been ravaged by Swedish armies. One year later, in November 1659, the Poles and Dutch together with Danish and Prussian troops defeated the Swedes at the Battle of Nyborg, in Denmark. The Dutch naval force was commanded by admiral Michiel de Ruyter, while the Polish armies were led by general Stefan Czarniecki. Several poets pictured the Dutch and Poles as close allies, including the famed Joost van den Vondel, who wrote: “See how the eagles and proud lions strike their talons and claws in the heart of the Swedes.”

In 1660, the death of king Karl X Gustav of Sweden hastened the end of the Second Northern War.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 46.