This time of year, many of us have a nativity scene in our homes. They commonly include the Three Kings, also known as Wise Men or Magi, who came to honour Christ after his birth. These Kings are often dressed in long oriental robes and turbans. What is less commonly known, is that such a look in the previous centuries was sometimes associated with Polish dress. This can be exemplified by a gable stone showing a ‘Pool’, which is dated 1688, and which adorns a building on the Kerkstraat 322 in Amsterdam.

This time of year, many of us have a nativity scene in our homes. They commonly include the Three Kings, also known as Wise Men or Magi, who came to honour Christ after his birth. These Kings are often dressed in long oriental robes and turbans. What is less commonly known, is that such a look in the previous centuries was sometimes associated with Polish dress. This can be exemplified by a gable stone showing a ‘Pool’, which is dated 1688, and which adorns a building on the Kerkstraat 322 in Amsterdam.

During the sixteenth century, Polish male fashion became increasingly influenced by Persian and Ottoman examples, leading Polish noblemen to wear colourful leather boots with heels, a kontusz (a coat or outer kaftan), a ferezja or delia (different types of cloaks), worn over a long-sleeved żupan (a tunic), and a kołpak (a hat often embellished with fur and feathers). Dutch artists and artisans subsequently produced multiple images of ‘typical’ Polish nobles, for example in books, on maps, and… on gable stones. To Dutch eyes, however, Polish dress differed very little – if at all – from other Eastern fashion: Polish figures were also used to represent Hungarians, for example. Similarly, Polish figures were sometimes indistinguishable from Ottomans.

Interestingly, the French diplomat Charles Ogier, who visited Poland in the 1630s, likewise associated Polish fashion with the Three Kings. Describing a host of Polish nobles, he compared them to “the Eastern Magi, who came to honour the Infant Jesus with a large measure of display.”

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 24.

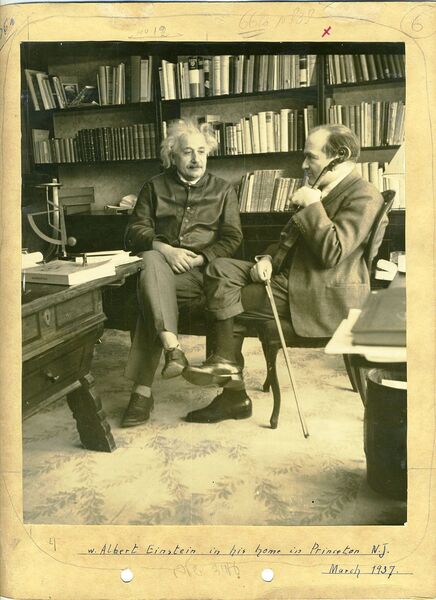

Last week, it was announced that the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam – with financial aid from the Dutch state and several institutions – intends to buy ‘The Standard Bearer’, a painting by Rembrandt from 1636. Such standard bearers were high-placed members of town militias, not necessarily soldiers. Still, the painting offers an opportunity to reflect on a little-known aspect of Dutch-Polish historical relations: Polish soldiers in the seventeenth-century Dutch army. A travel account by the Pole Sebastian Gawarecki, written during the 1640s, discusses his stay in the Northern Netherlands alongside Marek and Jan Sobieski – the later king of Poland. On 16 May 1646, in the town of Bergen op Zoom, Gawarecki and the Sobieski brothers met “a Pole from Warsaw, who for some years now serves in the Dutch army as a standard bearer, and whom our Polish king [Władysław IV Waza] keeps in Holland at his own expense.” It is unknown who this Polish standard bearer was, but it was not unheard of for Poles to fight in the Dutch army, even if they were Catholics.

Last week, it was announced that the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam – with financial aid from the Dutch state and several institutions – intends to buy ‘The Standard Bearer’, a painting by Rembrandt from 1636. Such standard bearers were high-placed members of town militias, not necessarily soldiers. Still, the painting offers an opportunity to reflect on a little-known aspect of Dutch-Polish historical relations: Polish soldiers in the seventeenth-century Dutch army. A travel account by the Pole Sebastian Gawarecki, written during the 1640s, discusses his stay in the Northern Netherlands alongside Marek and Jan Sobieski – the later king of Poland. On 16 May 1646, in the town of Bergen op Zoom, Gawarecki and the Sobieski brothers met “a Pole from Warsaw, who for some years now serves in the Dutch army as a standard bearer, and whom our Polish king [Władysław IV Waza] keeps in Holland at his own expense.” It is unknown who this Polish standard bearer was, but it was not unheard of for Poles to fight in the Dutch army, even if they were Catholics.

Joris’s representation of Poland is generally favourable. Describing Cracow, he professed that: “it lies along the Vistula river, which also flows past the royal castle, placed on an elevated mound. Because of the splendour of its buildings, the affluence of all manner of goods, and various kinds of scholarly disciplines, the city itself contends with the illustrious towns of Germany.” In addition, Joris enthusiastically related his visit to the nearby Wieliczka salt mines, which attracted the attention of various foreign scholars and travellers. He also visited the poet Szymon Szymonowicz (1558-1629) in Lviv, and he befriended a Polish diplomat in Constantinople, who shared his interest for classical literature. Returning home, furthermore, Joris stayed in Zamość, a city founded in 1580 by the Grand Chancellor Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605), who was a friend of Joris’s father. Zamość also included an academy for higher education. Joris elaborately praised the city as “an effigy not just to Poland, but to the whole of Europe”, and he applauded the learnedness of Zamoyski himself. His flattering words were no doubt meant to strengthen his bonds with his Polish contacts. The account is an interesting testimony to the historical ties and friendships between Dutch and Polish scholars.

Joris’s representation of Poland is generally favourable. Describing Cracow, he professed that: “it lies along the Vistula river, which also flows past the royal castle, placed on an elevated mound. Because of the splendour of its buildings, the affluence of all manner of goods, and various kinds of scholarly disciplines, the city itself contends with the illustrious towns of Germany.” In addition, Joris enthusiastically related his visit to the nearby Wieliczka salt mines, which attracted the attention of various foreign scholars and travellers. He also visited the poet Szymon Szymonowicz (1558-1629) in Lviv, and he befriended a Polish diplomat in Constantinople, who shared his interest for classical literature. Returning home, furthermore, Joris stayed in Zamość, a city founded in 1580 by the Grand Chancellor Jan Zamoyski (1542-1605), who was a friend of Joris’s father. Zamość also included an academy for higher education. Joris elaborately praised the city as “an effigy not just to Poland, but to the whole of Europe”, and he applauded the learnedness of Zamoyski himself. His flattering words were no doubt meant to strengthen his bonds with his Polish contacts. The account is an interesting testimony to the historical ties and friendships between Dutch and Polish scholars.

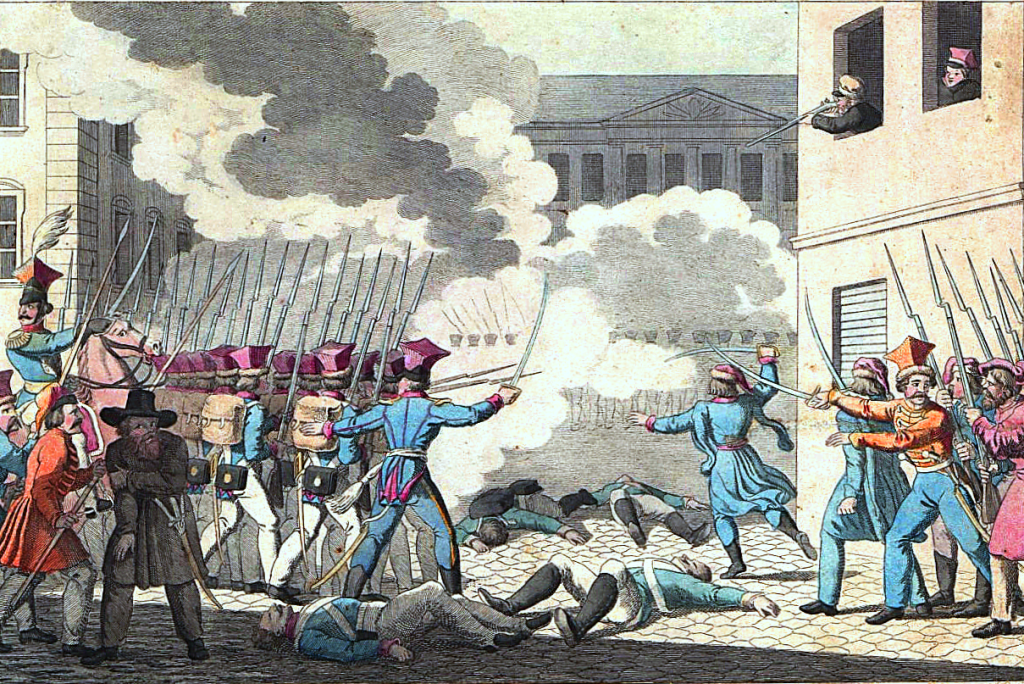

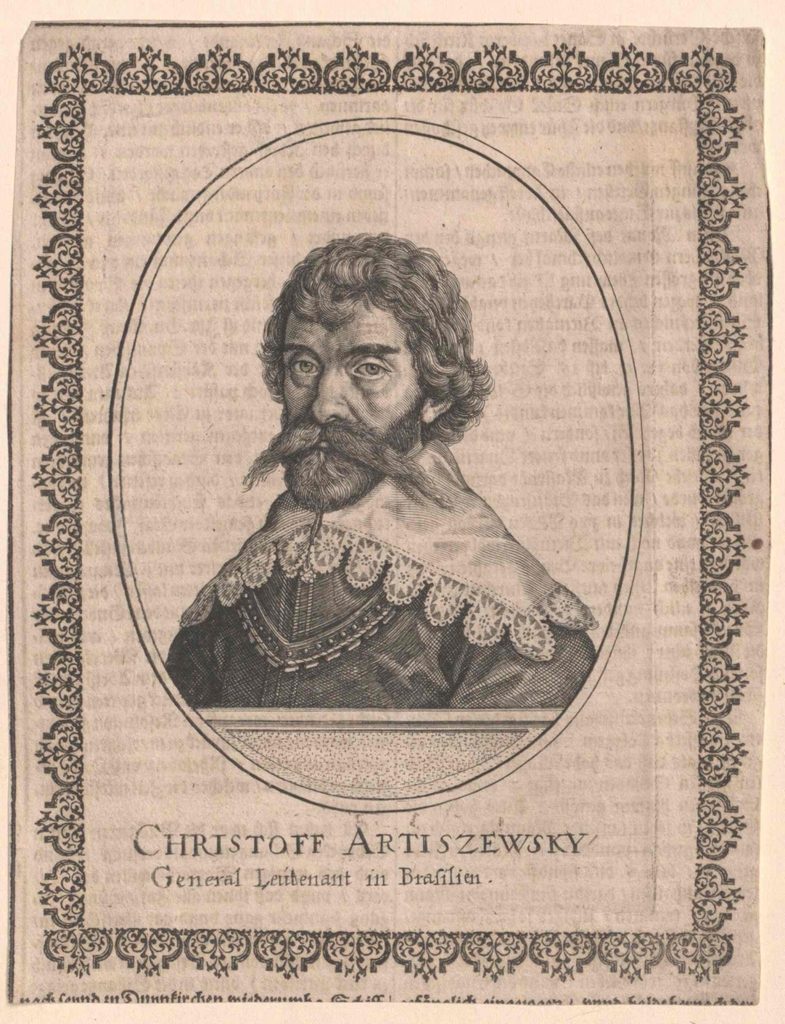

Numerous Poles live and work in the Netherlands today, and they have been doing so for hundreds of years. One of the most colourful and famous examples is the Protestant nobleman Krzysztof Arciszewski (1592-1656), an officer, engineer and author, who through became something of a celebrity in both the seventeenth-century Netherlands and Poland. Arciszewski first arrived in Holland in 1624, at the time of the Eight Years’ War, and until 1629 actively participated in a number of battles in both the Low Countries and France, always fighting on the Protestant side. For example, he partook in the Dutch attempts to end the Spanish siege of Breda in 1624-1625, and he fought in the siege of ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1629. Moreover, he studied military engineering and artillery at Leiden University. In 1629, Arciszewski was offered a three-year contract with the Dutch West-India Company and in the rank of captain left for Brazil. He celebrated multiple victories against the Portuguese, and was eventually promoted colonel. After the arrival, in 1637, of the new governor-general, Count John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), Arciszewski continued to play a key role in the Brazilian campaign, but disagreements between the two men led to Arciszewski’s return to Holland in 1639. He broke with the Dutch military, but stayed in the United Provinces until 1646, at which time he was summoned back to Poland and nominated royal general of artillery. Arciszewski next participated in a number of battles against the Turks and Cossacks, before retiring in 1649. He died in 1656.

Numerous Poles live and work in the Netherlands today, and they have been doing so for hundreds of years. One of the most colourful and famous examples is the Protestant nobleman Krzysztof Arciszewski (1592-1656), an officer, engineer and author, who through became something of a celebrity in both the seventeenth-century Netherlands and Poland. Arciszewski first arrived in Holland in 1624, at the time of the Eight Years’ War, and until 1629 actively participated in a number of battles in both the Low Countries and France, always fighting on the Protestant side. For example, he partook in the Dutch attempts to end the Spanish siege of Breda in 1624-1625, and he fought in the siege of ’s-Hertogenbosch in 1629. Moreover, he studied military engineering and artillery at Leiden University. In 1629, Arciszewski was offered a three-year contract with the Dutch West-India Company and in the rank of captain left for Brazil. He celebrated multiple victories against the Portuguese, and was eventually promoted colonel. After the arrival, in 1637, of the new governor-general, Count John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), Arciszewski continued to play a key role in the Brazilian campaign, but disagreements between the two men led to Arciszewski’s return to Holland in 1639. He broke with the Dutch military, but stayed in the United Provinces until 1646, at which time he was summoned back to Poland and nominated royal general of artillery. Arciszewski next participated in a number of battles against the Turks and Cossacks, before retiring in 1649. He died in 1656.