Many Dutchmen and -women strongly support the Ukrainians in their fight against Russian aggression. A comparable situation occurred over two hundred years ago, in 1794, when the young Dutch poet David Jacob van Lennep spoke out in support of the Poles, who fought for freedom and independence. The Polish general Tadeusz Kościuszko at that time led an armed uprising to defend his country’s territorial integrity and autonomy, a year after the Second Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. The image shows Kościuszko’s Proclamation, a painting by Franciszek Smuglewicz depicting a speech Kościuszko gave in Cracow in March 1794, which is considered the beginning of the uprising.

Van Lennep responded to the uprising with two long poems. One celebrates an important Polish victory in September 1794, when the Siege of Warsaw by Russian and Prussian forces was lifted. The other composition carries the title “Lyre Song to the Poles”, and is dated May 1794. Van Lennep rejoices in the Polish uprising and slanders the Russian and Prussian oppressors. He enthusiastically describes how the Poles defend their freedom, which is threatened by the “tigress of the north” – Catherine II of Russia, known as the Great – and the “treacherous” Prussians, who lay waste to Polish lands and murder and enslave the population. “Legitimizing violence with the appearance of justice / Strengthens tyrants’ crowns, / And accusing innocent people of terrible deeds / Solidifies the foundations of their thrones,” Van Lennep wrote – words which would be just as appropriate today.

Furthermore, Van Lennep compares the Polish uprising with the Dutch fight against Spain during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. He heralds “the crowds of Polish heroes” as the bringers of freedom for all oppressed peoples and foreshadows that the aggressors will flee, thus “trampling Russia’s honor in the dust”. Lastly, Van Lennep expresses the certainty that Poland will once again prosper, and he asks God for universal peace and freedom.

Kościuszko’s uprising sadly did not end well for the Poles, who were eventually defeated by Russian and Prussian forces. The following year, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was conclusively partitioned out of existence by Russia, Prussia, and Habsburg Austria. Van Lennep, meanwhile, went on to become professor of Latin and Greek in Amsterdam, as well as a respected poet. Years later, he wrote that he never regretted supporting the Poles, who had been “treated with terrible injustice, which filled me with indignation”.

Just as Van Lennep did in 1794, we must continue to speak out against Russian aggression.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 33.

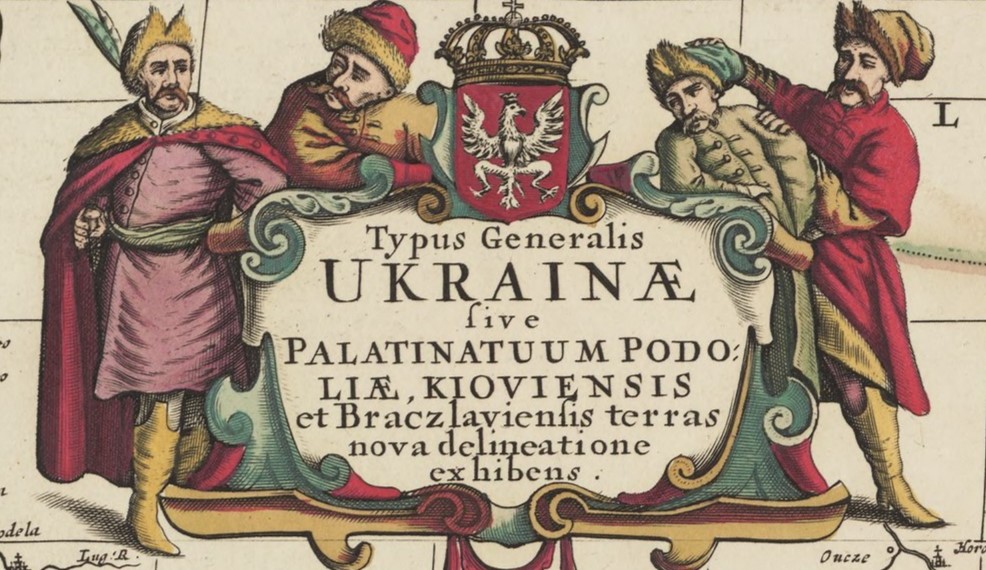

In July 1606, a young student called Samuel Korecki inscribed his name into the album amicorum (“book of friends”) of the Dutch scholar and mayor of Harderwijk, Ernst Brinck. Korecki’s name features amongst numerous well-known men of the time, such as Galileo Galilei. But who was he?

In July 1606, a young student called Samuel Korecki inscribed his name into the album amicorum (“book of friends”) of the Dutch scholar and mayor of Harderwijk, Ernst Brinck. Korecki’s name features amongst numerous well-known men of the time, such as Galileo Galilei. But who was he?

This time of year, many of us have a nativity scene in our homes. They commonly include the Three Kings, also known as Wise Men or Magi, who came to honour Christ after his birth. These Kings are often dressed in long oriental robes and turbans. What is less commonly known, is that such a look in the previous centuries was sometimes associated with Polish dress. This can be exemplified by a gable stone showing a ‘Pool’, which is dated 1688, and which adorns a building on the Kerkstraat 322 in Amsterdam.

This time of year, many of us have a nativity scene in our homes. They commonly include the Three Kings, also known as Wise Men or Magi, who came to honour Christ after his birth. These Kings are often dressed in long oriental robes and turbans. What is less commonly known, is that such a look in the previous centuries was sometimes associated with Polish dress. This can be exemplified by a gable stone showing a ‘Pool’, which is dated 1688, and which adorns a building on the Kerkstraat 322 in Amsterdam. This is why the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam looks the way he does. His clothing – which even includes a turban – and his posture are reminiscent of a man in a print by the Dutch engraver Lucas Vorsterman, after the Adoration of the Magi by the famed painter Peter Paul Rubens, a painting from 1621. Rubens in turn based himself on Italian illustrations. It is likely that the gable stone’s maker referred to the same pictorial tradition. This is how the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam is related to nativity scenes.

This is why the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam looks the way he does. His clothing – which even includes a turban – and his posture are reminiscent of a man in a print by the Dutch engraver Lucas Vorsterman, after the Adoration of the Magi by the famed painter Peter Paul Rubens, a painting from 1621. Rubens in turn based himself on Italian illustrations. It is likely that the gable stone’s maker referred to the same pictorial tradition. This is how the ‘Pool’ on the gable stone in Amsterdam is related to nativity scenes.