Have you been to the Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam? The exhibition includes 28 of the 37 known paintings by the 17th-century Dutch master: the largest collection of Johannes Vermeer’s works ever brought together in a museum. His paintings have long since captured peoples’ imaginations, however. For example, several Polish poets have been inspired to write verses about Vermeer’s works. Two well-known authors who did so are Adam Czerniawski and Adam Zagajewski. The latter wrote a number of poems about or featuring Vermeer, such as “Vermeer’s Little Girl”, which describes the famous “Girl with a Pearl Earring”.

Moreover, both Czerniawski and Zagajewski composed poems about Vermeer’s “View of Delft”: a panorama of the city where the painter lived and worked, made in ca. 1660-1661. Czerniawski’s poem dates from 1969. It begins as follows:

“In The Hague there is a view of Delft,

In The Hague there is a perspective of Delft,

All it takes to see Delft,

Is to reach the first floor of the Mauritshuis,

Where the panorama is not obstructed by

A hill or a broad chestnut tree.”

The poet speaks of two views of Delft: the modern one, which is made of “steel and glass”, and the 17th-century one, captured on canvas. In the rest of the poem, Czerniawski considers his own relationship with – and desire to witness – these two “Delfts”, and tries to describe both the painting and the city itself.

The poem by Zagajewski dates from 1983. It is much shorter:

“Houses, waves, clouds, and shadows

(dark-blue roofs, brown bricks):

at last, you have become but a glance.

The uncontrolled, calm eyes of objects,

glittering with blackness.

You will outlive our admiration, our tears,

and our noisy, despicable wars.”

In but a few sentences, Zagajewski presents the painting as an everlasting ideal, which observes the ever-changing, cruel world.

We wish a lovely time to those of you who are fortunate enough to have a ticket for the exhibition, where you can see Vermeer’s “View of Delft” for yourselves. Don’t worry if you didn’t get a ticket: you can see the painting in the Mauritshuis in The Hague after the exhibition in Amsterdam ends. And who knows, maybe you will be inspired to write your own poems!

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 43.

Poland and the Netherlands share a rich history in sports. Right now, for instance, the two countries together host the Volleyball World Championship for women. An interesting older Dutch-Polish connection relating to women’s sports dates from 1928, when Amsterdam hosted the Summer Olympics. It was the first time women were allowed to participate in athletic and gymnastic events at the Olympic competition. The world champion in the field of discus throwing, the Polish Halina Konopacka, won the gold medal in that discipline, smashing both her personal and the world records. In addition, it was the first Olympic gold medal ever won on behalf of Poland. Konopacka was considered a beautiful athlete, which earned her the nickname “Miss Olympia”.

Poland and the Netherlands share a rich history in sports. Right now, for instance, the two countries together host the Volleyball World Championship for women. An interesting older Dutch-Polish connection relating to women’s sports dates from 1928, when Amsterdam hosted the Summer Olympics. It was the first time women were allowed to participate in athletic and gymnastic events at the Olympic competition. The world champion in the field of discus throwing, the Polish Halina Konopacka, won the gold medal in that discipline, smashing both her personal and the world records. In addition, it was the first Olympic gold medal ever won on behalf of Poland. Konopacka was considered a beautiful athlete, which earned her the nickname “Miss Olympia”. On this day in 1869, the city of Groningen witnessed a wondrous spectacle: the re-enactment of the entrance of King Jan III Sobieski of Poland into Vienna, in September 1683. At 7 pm, a masquerade of over seventy lavishly clad Dutch students began its passage through the city center, both on foot and on horseback. Such student masquerades were a common phenomenon in the nineteenth-century Netherlands, and they often portrayed specific historical events. An accompanying booklet enthusiastically relates Sobieski’s victory over the Turks at the Battle of Vienna, on 12 September 1683, and it also lists the masquerade’s participants, the roles they played, and the route they took through Groningen. Moreover, the booklet contains a small print based on a larger, colored illustration by the local artist Otto Eerelman. It depicts the masquerade as a long string of men in historical costumes of Polish and Austrian or German soldiers and clergymen, many wielding sabers, war hammers, lances, and flags. At the center of the print stands the masquerade’s main figure: Sobieski. Naturally, the print gives a fictional impression of the event, but one can imagine the excitement the masquerade must have caused in Groningen, which for one evening in 1869 played the role of Vienna welcoming Jan III Sobieski in 1683.

On this day in 1869, the city of Groningen witnessed a wondrous spectacle: the re-enactment of the entrance of King Jan III Sobieski of Poland into Vienna, in September 1683. At 7 pm, a masquerade of over seventy lavishly clad Dutch students began its passage through the city center, both on foot and on horseback. Such student masquerades were a common phenomenon in the nineteenth-century Netherlands, and they often portrayed specific historical events. An accompanying booklet enthusiastically relates Sobieski’s victory over the Turks at the Battle of Vienna, on 12 September 1683, and it also lists the masquerade’s participants, the roles they played, and the route they took through Groningen. Moreover, the booklet contains a small print based on a larger, colored illustration by the local artist Otto Eerelman. It depicts the masquerade as a long string of men in historical costumes of Polish and Austrian or German soldiers and clergymen, many wielding sabers, war hammers, lances, and flags. At the center of the print stands the masquerade’s main figure: Sobieski. Naturally, the print gives a fictional impression of the event, but one can imagine the excitement the masquerade must have caused in Groningen, which for one evening in 1869 played the role of Vienna welcoming Jan III Sobieski in 1683. On 12 September 1683, King Jan III Sobieski of Poland achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Vienna. In July that year, Turkish forces had laid siege to the imperial city as part of a campaign designed to strengthen the Ottoman Empire’s influence in Europe. Emperor Leopold I allied himself with Sobieski, who rode to Vienna’s aid and took command of the city’s relief. After the final battle took place, the Turks were routed and forced to retreat, eventually losing their foothold in Hungary and Transylvania.

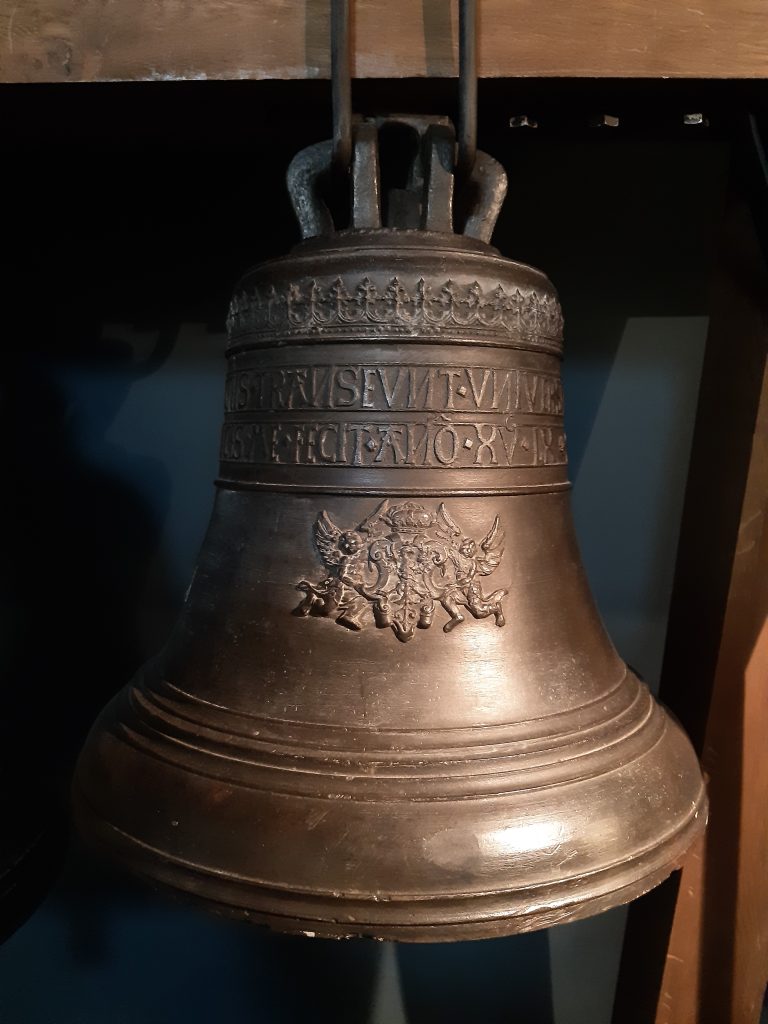

On 12 September 1683, King Jan III Sobieski of Poland achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Vienna. In July that year, Turkish forces had laid siege to the imperial city as part of a campaign designed to strengthen the Ottoman Empire’s influence in Europe. Emperor Leopold I allied himself with Sobieski, who rode to Vienna’s aid and took command of the city’s relief. After the final battle took place, the Turks were routed and forced to retreat, eventually losing their foothold in Hungary and Transylvania. At this moment, the city of Gdańsk is busy hosting its annual Carillon Festival. An interesting example of the cultural relations between the Netherlands and Poland concerns the carillons in Gdańsk. In 1561, a carillon consisting of 14 bells was installed in the new tower of the Main Town Hall. The bells had been cast the previous year in ’s-Hertogenbosch, Brabant, by the bell-founder Johannes Moor. Together, they made up the oldest carillon outside the Low Countries. Each bell was adorned with the coat of arms of Gdańsk, Prussia and Poland, and carried a Latin sentence: “Time covers the whole world and everything under heaven passes in its spaces. Johannes Moor from ’s-Hertogenbosch made me in the year 1560.” Every hour, the carillon played two alternating melodies, which were changed weekly according to the liturgical calendar. Furthermore, a second carillon from the Northern Netherlands was installed in St. Catherine’s Church during the eighteenth century. It was cast by Johann Nicolaus Derck in Hoorn, Holland.

At this moment, the city of Gdańsk is busy hosting its annual Carillon Festival. An interesting example of the cultural relations between the Netherlands and Poland concerns the carillons in Gdańsk. In 1561, a carillon consisting of 14 bells was installed in the new tower of the Main Town Hall. The bells had been cast the previous year in ’s-Hertogenbosch, Brabant, by the bell-founder Johannes Moor. Together, they made up the oldest carillon outside the Low Countries. Each bell was adorned with the coat of arms of Gdańsk, Prussia and Poland, and carried a Latin sentence: “Time covers the whole world and everything under heaven passes in its spaces. Johannes Moor from ’s-Hertogenbosch made me in the year 1560.” Every hour, the carillon played two alternating melodies, which were changed weekly according to the liturgical calendar. Furthermore, a second carillon from the Northern Netherlands was installed in St. Catherine’s Church during the eighteenth century. It was cast by Johann Nicolaus Derck in Hoorn, Holland.

The plot can be summarized as follows. The Polish king Basilius keeps his son Sigismundus locked in a tower, as he believes in a prophecy which states that his son will bring the country to ruin. One day, Sigismundus is set free and claims his father’s throne, but his behaviour is so beastly that he is once again imprisoned. He is released by Polish rebels, however, who prefer him to his rival, a Muscovite prince. Bloodshed follows, but when Sigismundus realizes the cruelty of his actions, he offers his father his services. Impressed, Basilius surrenders the crown to Sigismundus.

The plot can be summarized as follows. The Polish king Basilius keeps his son Sigismundus locked in a tower, as he believes in a prophecy which states that his son will bring the country to ruin. One day, Sigismundus is set free and claims his father’s throne, but his behaviour is so beastly that he is once again imprisoned. He is released by Polish rebels, however, who prefer him to his rival, a Muscovite prince. Bloodshed follows, but when Sigismundus realizes the cruelty of his actions, he offers his father his services. Impressed, Basilius surrenders the crown to Sigismundus.