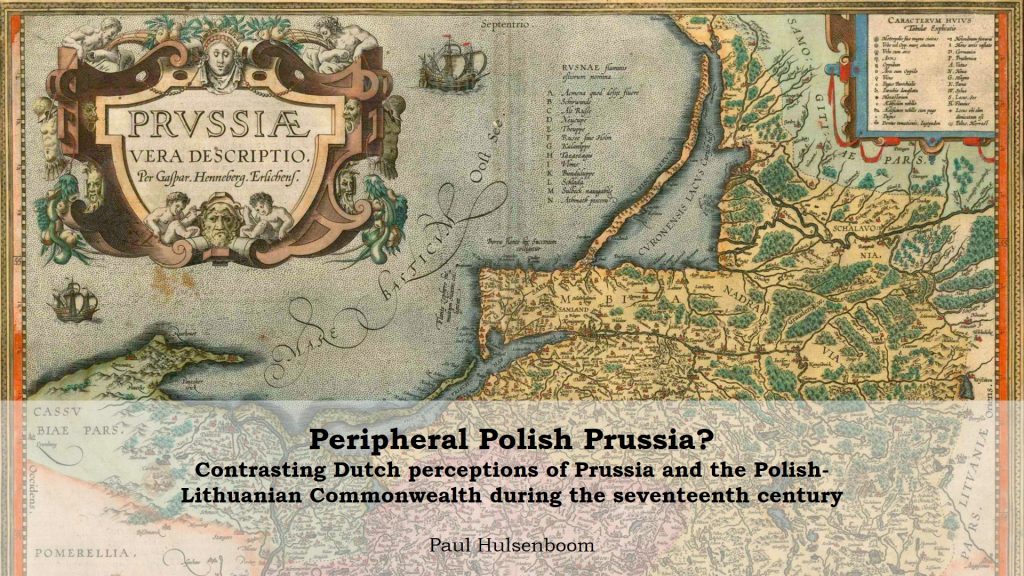

On 15 November, I gave a paper presentation at Radboud University’s international conference Is Europe Inclusive? Together with prof. dr. Marguérite Corporaal, I organised a panel on conceptions of European centres and peripheries throughout the ages. In my paper, entitled Peripheral Polish Prussia? Contrasting Dutch Perceptions of Prussia and the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth during the seventeenth century, I argued that notions of centres and peripheries are ever changing and dependent on the observer. I used the case of Prussia, which during the nineteenth century was framed as the centre of Germanness, but which nowadays no longer exists as a geographic entity.

In my presentation, I posed the question how Prussia was perceived before its rise to power as an independent state, when during the seventeenth century it was under Polish rule. Royal Prussia, with Danzig as its most important port, was an integral part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 to 1772, while Ducal Prussia was a vassal of the Polish king from 1525 until 1660. The observers I chose, the Dutch, had strong economic and cultural ties with Prussia. Did the Dutch view Prussia, which was culturally similar to the Low Countries and of great economic importance to the Dutch Republic, as a centre, or rather as a periphery and a mere province within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth?

Using a variety of sources, I made clear that the Dutch had differing opinions about the region: while some sources preferred Prussia to Poland proper, saying that Prussian houses and grain were superior to Poland’s, other sources paint a different picture. Abraham Booth, who wrote the first Dutch eyewitness account of Poland-Lithuania, printed in Amsterdam in 1632, wrote an unflattering report of his journey through both Prussia and Poland. Negative elements were, for example, vast forests, cruel Polish soldiers, bad roads and shabby accommodations. This presentation is hardly surprising, as Booth wrote his account during a diplomatic mission to Prussia, in which the Dutch mediated between the Swedes and Poles after the Swedes had invaded Polish territory. The Dutch were officially allied with the Swedes, however. On the other hand, Poland and Prussia always feature favourably in the works of Joost van den Vondel, the most prominent Dutch poet of the seventeenth century. Vondel saw Prussia as belonging to Poland, and repeatedly praised the Commonwealth for its fertility and the role it played as a bulwark of Christendom. This no doubt had to do with Vondel’s Catholic sympathies. In this way, I hope to have shown that what constitutes a centre or a periphery is not fixed and easily measurable, but rather depends on the historical context and background of the observer.