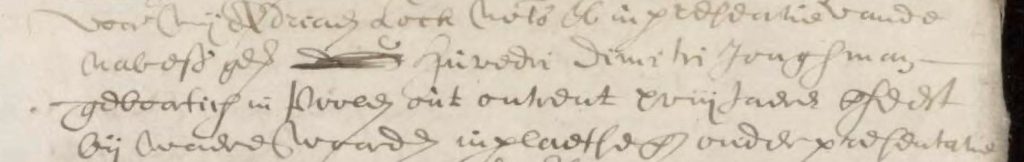

Historians keep finding new sources and telling new stories, which enrich our views of the past and of the present. One recently uncovered tale concerns a young enslaved Pole, who came to Holland in the seventeenth century. Fragmentary traces of his life are preserved in the city archives of Amsterdam, which house countless old documents. Notary deeds from November 1656 introduce him as “a young man called Huvedi Dimitri, born in Poland and about 18 years of age”. He called upon the local notary Adriaen Lock and in the presence of several merchants and interpreters revealed that he had been living in slavery in the Ottoman Empire. Dimitri had been enslaved when he was about 10 years old. Some 15 months ago, a merchant from Aleppo called Joan Elias had bought him in Smirna (Izmir).

Dimitri had come to Holland as Elias’s slave, but had heard that there was no such thing as slavery in Amsterdam. A Greek merchant named Augustus de Miter had convinced him that Holland was “a free country”. He urged Dimitri to leave his master, and was willing to reimburse Joan Elias for Dimitri’s freedom. De Miter even wanted to give the Polish boy some money, so that he might travel home to his family. Just to be sure, he “violently” dragged him to a church and made him swear his tale was true. Some time later, Joan Elias visited another notary in Amsterdam, declaring that he would “set his slave free once more, relieving him of all servitude and slavery”. This may be a reference to Dimitri.

Much remains unclear about Huvedi Dimitri. The sources say he was “born in Poland”, and he may have identified himself as Polish as well, but what that would mean and where exactly he came from is uncertain. Dutch definitions of “Poland” could refer to the eponymous Kingdom or to the entire Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and notions of nationality were fuzzier than they are now. Perhaps Dimitri was born in the southern lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In those territories, most of which belong to modern-day Ukraine, Tatars frequently performed raids and enslaved the local population. Dimitri may have been captured during such a raid and then sold on to someone in the Ottoman Empire. His name, which of course is not Polish, may have been given to him in captivity.

To this day, most of what we know about the presence of Poles in seventeenth-century Holland focuses on free and wealthy noblemen. The notary deeds from Amsterdam offer a valuable new perspective on less fortunate individuals from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who could also reach Holland, but had entirely different experiences. In addition, Dimitri’s story shows that slavery in Amsterdam was not condoned.

The notary deeds were found by historian Mark Ponte. For more information, see his blog post.