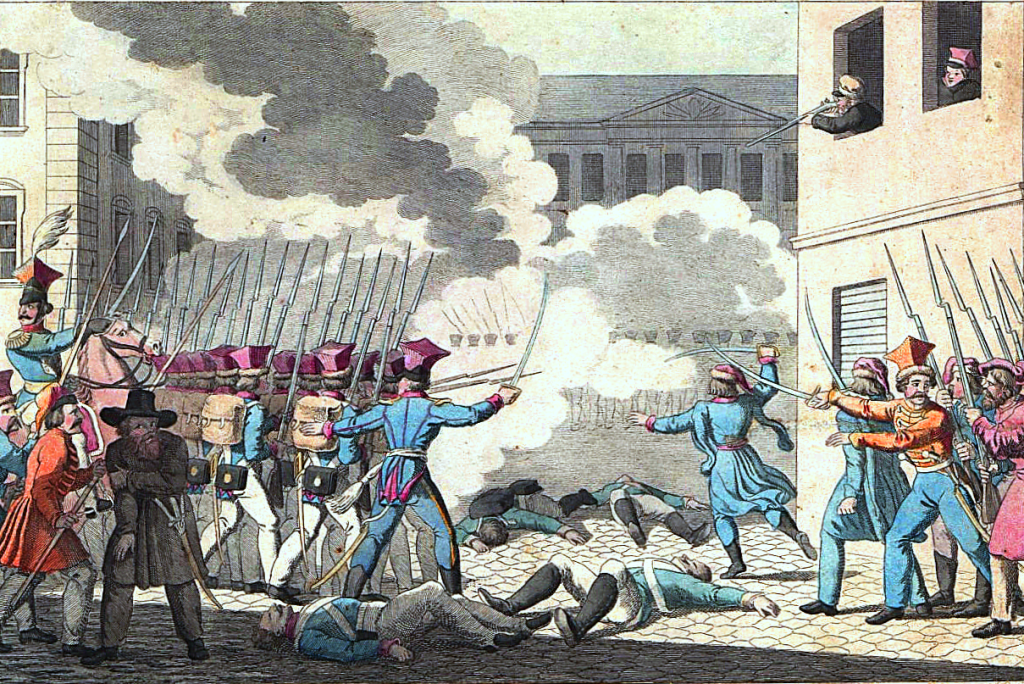

In the night of 29 November 1830, the November Uprising began. Polish soldiers in Warsaw started a revolt against the Russian Empire, which had taken control of large parts of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The uprising sparked considerable interest in the Netherlands. But whereas writers in most other European countries supported the Polish insurgents, Dutch responses condemned the revolution altogether. Poems and treatises by various Dutch authors eulogised the Russian tsar as a benevolent ruler, and simultaneously slighted the Poles for their so-called ungratefulness. In addition, they defined the Poles as principally chaotic and unruly.

Why were the Dutch so dismissive of the November Uprising? The answer lies in the Belgian Revolution, which had started in Brussels in August 1830 and in November that year led to the establishment of the National Congress of Belgium. The southern Netherlandish provinces thus separated themselves from their northern neighbours. Many Dutch observers were disgruntled with this situation, and subsequently also criticized the Polish insurrectionists, who they accused of being misled by harmful French influences. Indeed, some authors even stated that if the Poles had not revolted, the Russian tsar surely would have gone to war in order to set things right in Belgium as well.

Other than the Belgian Revolution, the November Uprising did not result in an independent Polish state. By October 1831, the revolt was crushed, and the Russian grip on Poland became even stronger. Dutch responses to Poland’s struggle for autonomy became more nuanced with time, however, and during the January Uprising of 1863-64, many Dutch voices supported the Poles. Belgian historian Idesbald Goddeeris has argued, therefore, that nineteenth-century Dutch responses to Poland shifted according to local Dutch interests.

For more information, see this webpage.

*I originally wrote this post for the social media outlets of the Dutch Embassy in Poland. This was post no. 22.